I was barely fourteen years old when my father and I were arrested for the crime of destitution. The long walk to London had enfeebled us to the point of near insensibility, and that we found my uncle’s house at all was close to miraculous, just as inebriates often seem to be guided safely to their beds by angels, having subsequently no memory of the journey. There our luck had ended. We were received at the side entrance like particularly poor applicants for a vacancy below stairs. A vinegar-lipped housekeeper bade us wait for the master in the kitchen, but it was not my uncle who came but the traps. We were carried to the Sponging-house immediately, without the opportunity of either rest or sustenance.

I have little recollection of my uncle’s dwelling, other than a vague impression of affluence, but the Sponging-house I remember clearly. It was a terraced house fortified, I knew not where at the time, with heavy locks on the doors and bars on the windows. We were conveyed to an unfurnished upstairs room by a bailiff and advised to send for money, as there was rent to pay on our new lodgings. Having nowhere else to turn, my father requested that word be sent to his brother-in-law, although under the circumstances any assistance from that quarter seemed highly unlikely. My father preferred to give my uncle the benefit of the doubt, speculating that we must have been followed from home by Grimstone’s agents. It was my private belief that he was most likely in collusion with our enemy, and had dobbed us in himself.

My conjecture was largely confirmed when my uncle deigned to visit a couple of days later, in the company of the equally traitorous housekeeper. He shared my mother’s eyes, but there any resemblance ceased. He had about him the same pinched look of arrogance and abstinence as his woman, in the way that dogs often resemble their masters, and to my fevered eyes they appeared as a pair of darkly accoutred weasels.

No one shook hands and my uncle did not bother to remove his hat. ‘I knew you would come to this in the end,’ he said, addressing my father. ‘Did you think to outrun your creditors by coming to me?’

‘I thought you might help my children,’ replied my father, with admirable control. ‘But I see now that I was mistaken.’

My uncle then briefly directed his attention to me. ‘You look like your father,’ he said, in the manner of the foreman of a jury delivering a verdict of ‘Guilty.’

I was too weak to respond, but he had already turned away. I was evidently considered well beyond redemption by virtue of nothing more than my countenance. They both seemed more interested in my sister, who the housekeeper had swept up in her skeletal arms without invitation or consent. Sarah was horrified, and was twisting and screaming like a child of the fairy mounds. That’s my girl, I thought.

Undeterred by this obvious hostility, the woman looked knowingly at my uncle, although she said not a word. ‘We will take the girl,’ he said.

‘No!’ I cried, forgetting myself.

‘Be quiet, boy,’ said my uncle, fetching me a powerful blow across the face. I did as I was told and shut up. He turned to my father. ‘She will be safe from the gaol fever with us,’ he said, as if nothing untoward had happened, ‘as well as the pernicious influence and perverted attentions of other prisoners.’

‘We will see that she is well established in Society,’ added the housekeeper, keeping a tight hold on my still protesting sister.

My uncle’s face seemed to soften at the sound of the woman’s voice. ‘She will have a much better lot in life in our care,’ he said.

My father did not even pause to consider the offer. ‘Jack,’ he said, in an uncharacteristically authoritative voice that was, just for that instant, more than the equal of my uncle’s hectoring tone, ‘your sister is upset, please attend to her.’ I rose quickly and took possession of Sarah before the woman could react. She stopped crying and settled contentedly in my arms. I moved to my father’s side. ‘I will leave no child of mine under such a bleak roof as yours,’ he told my uncle. The woman seemed to hiss, but said nothing coherent, and my father continued. ‘It seems safe enough, I grant you,’ he said, ‘but it looks to me a joyless home in which to grow, and Sarah is such a bright and happy child.’

‘Then the Devil take you, sir,’ said my uncle, ‘for I’ll have no more of you.’ And with that, the austere couple took their leave.

‘The Devil take you too, Judas,’ I whispered in his wake.

My father slumped against the wall and slid slowly to the bare wood floor. ‘I know I’m selfish, son,’ he said quietly, ‘but I couldn’t do without her.’

I sat down beside him and managed a smile, letting Sarah crawl between us. ‘It’s like Mum used to say,’ I told him, ‘love will always hold much more value in our family than money.’

‘Then I am rich indeed,’ said he, doing his best to return my lopsided grin, ‘but I fear our creditors will not accept it.’

*

Soon after, we moved from the Sponging-house to the main prison with very little ceremony, there being no way to settle our debts, which, in my father’s case, were huge. My lawyer’s bill was not so extreme, amounting only to a pound, but it was a quid more than we had, and our debts increased daily by virtue of our continued habit of breathing, like a tax upon fresh air.

As Dickens has written, at considerable length, and in finer terms than I ever could, the paradox of debtor’s prison was that you could not earn the money you so desperately needed in order to pay off your creditors from the inside. This penny plain yet devastating reality was another of those great and terrible jokes played upon the poor and vulnerable of our society by those that did and still do own and control it, just as the Great Architect torments us all with endless toil to no avail, incurable disease, old age, deformity, lost love, dead children, and an individual consciousness aware at all times of its inevitable demise. I would not have invented such things were I creating the universe, nor lawyers, politicians, or publishers neither. I would have left all that out of the grand celestial scheme of things, along with Newgate, the Fleet, and the bloody Marshalsea.

Like souls passing through the gates of Hell, those that entered the Marshalsea left all hope behind, although not all immediately realised that they had done so, or the desperate nature of their new situation. There were those, usually relatively young men, reasonably dressed and well spoken, who genuinely believed that the likely duration of their stay was to be so brief as to be hardly worth the bother of unpacking. These tragic optimists had not yet learned that in addition to meeting their creditor’s demands they must also pay for the privilege of incarceration, and that now denied access to the labour market, their initially modest debts would thus soon increase to small fortunes as unpaid prison fees accumulated alongside the interest on their debts, like the grains of wheat doubled upon each square of Ferdowsi’s chessboard. The only possibility of release from this grim spiral of debt, and therefore the prison, was to come into a large sum of money, which from the look of the majority of the inmates was about as likely as being twice struck by lightning on a clear summer day.

For those who still managed to obtain some sort of income, usually from family or friends, there was a thriving black economy that could provide anything from basic needs to comparative luxury. Rent on a good cell ranged from twenty to five hundred pounds per annum, and food, tobacco, whores, and strong drink were all available in house via the tap room (or ‘snuggery’), which functioned as a shop, bar and restaurant. Those that could afford to pay the turnkeys also received the best commodity of all, freedom, at least during the day, whereby they might work, although most earned only enough to meet their gaol costs rather than repay their creditors, so the vicious circle remained both intact and unbreakable.

Like all prisons, this one was dark, dank and overcrowded. When we were led through the great iron doors set in a high, spiked wall, we might as well have been entering Newgate. There was a small turnkey’s lodge by the entrance, and a dusty yard beyond it in front of the debtor’s section of the prison, which was a brick barracks built around a square, or ‘airing yard,’ with the look of a modern manufactory about it, the only difference being the bars on the windows.

That said, it could have been worse. The head turnkey, whose name I am ashamed to say I do not remember (Porter, possibly), provided us with a private room on the second floor which was quite light and almost airy by local standards, charging us only the most minimal of rents when, by rights, we could have been cast to the poor side of the barracks and left to rot in the meanest and most overcrowded of cells. This good man even waived the ‘garnish,’ a charge of five shillings and sixpence levied on all new prisoners. When news travelled that we had a motherless child, gifts of furniture, clothes, money, and even a few toys began to arrive from the generous people of Southwark. Because of the charity of the decent working poor, and the goodwill of our fellow insolvents, we were able to create quite a pleasant living space, albeit in a cell. The more we attempted to make things feel like home, though, the more we missed it. But our little cottage in the country was now lost to us forever, and with no hope of clearing my father’s debts beyond a miracle, we settled in for the long haul.

Little Sarah charmed everyone. She was then learning to walk and talk, and would hurtle around the courtyard unsteadily proclaiming wonder and fascination at the most quotidian of objects in a language known only to herself. Her burbling enthusiasm was infectious, and when she interacted with a fellow inmate you could see that invisible yoke of hopelessness that we all carried, like a wraith upon our shoulders, momentarily ease. Even the most hardened of cases, the ones who seemed born ugly, scarred and old, would pause to talk to her or even play. They called her the Child of the Marshalsea, and even though she was not born within those walls she might as well have been for the reverence in which she was held by the prison community.

The story that she had, indeed, been delivered there soon circulated and stuck in any case, as did the wink of the word from the senior members of the club, the real denizens of the London underworld with whom we shared the prison, that any man who harmed a single golden hair on her head would be cut in ways that would make him thereafter worthless to a woman. My father and I, meanwhile, were blessed by association. Dad became the Father of the Marshalsea, and he and I were similarly protected. And thus we gradually adapted to our new environment and community.

I tried to wear a brave face, and I put a singular amount of effort into concealing the secret agony of my soul from my poor father. None of these trials were of his own devising, after all; he was as innocent as my sister and myself. Like most of our fellow prisoners, we were merely victims of the free market. Memories of my happier childhood faded, and I felt my hopes of becoming a writer, a learned and distinguished man, crushed in my breast. My whole being was so penetrated by such rage, grief and humiliation that even years later, during the height of my literary celebrity, or even in the loving arms of my wife and child, my soul would always wander desolately back to that time in my life. My nature, my very essence, was formed within that blighted place, and I have never been truly free since.

I have heard tell that shipwrecked mariners often live or die in the water based upon the effort of their own will, and that at least in the first few hours it is not the cold or exhaustion that causes them to slip beneath the water and silently drown, but a conscious decision to surrender to despair. Others, no fitter or stronger, will equally resolve to stay alive for as long as possible in the hope of finding land or rescue. So it was with me. I chose to survive.

*

There were many classes of person in the Marshalsea, from unemployed labourers and artisans to redundant clerks and bankrupt swells, all in clothes that were out at the knees, arse and elbows. Eventually, my father set about repairing these raggedy men for food or a few pennies while I minded Sarah. Caring for her quickly became my reason to keep on kicking. Looking after such a gorgeous, vulnerable little bit of a person provided a routine that I had to follow, regardless of how I was feeling, and when I heard her little voice in the morning she became my motive for rising and getting through the day. Feeding, entertaining and chasing after a toddler from dawn to dusk, in the hope of tiring her enough for a peaceful night, as well as the endless changing and boiling of soiled napkins, also left me sufficiently exhausted to sleep, whatever the tempest within my head. I had resolved that no matter how angry, depressed or hopeless I might feel I would never display an ugly emotion in front of her (a rule I have also lately followed with my own child), and so I at least affected the appearance of a good humour and an even temper around the prison. This tended to count in my favour with the general population, some of whom were nutty enough upon me to make a gift of the odd penny or bit of bread.

There were many classes of person in the Marshalsea, from unemployed labourers and artisans to redundant clerks and bankrupt swells, all in clothes that were out at the knees, arse and elbows. Eventually, my father set about repairing these raggedy men for food or a few pennies while I minded Sarah. Caring for her quickly became my reason to keep on kicking. Looking after such a gorgeous, vulnerable little bit of a person provided a routine that I had to follow, regardless of how I was feeling, and when I heard her little voice in the morning she became my motive for rising and getting through the day. Feeding, entertaining and chasing after a toddler from dawn to dusk, in the hope of tiring her enough for a peaceful night, as well as the endless changing and boiling of soiled napkins, also left me sufficiently exhausted to sleep, whatever the tempest within my head. I had resolved that no matter how angry, depressed or hopeless I might feel I would never display an ugly emotion in front of her (a rule I have also lately followed with my own child), and so I at least affected the appearance of a good humour and an even temper around the prison. This tended to count in my favour with the general population, some of whom were nutty enough upon me to make a gift of the odd penny or bit of bread.

Sarah was still not yet two years old, and the benevolent influence of Mrs. McGuire had forged in her an easy going and adaptable temperament. She was, in a word, a joy. She could amuse herself for hours investigating odds and ends about the room, or communing with a wooden soldier that some kind soul had donated. She was fit and strong, and determined to live; she would eat whatever was available without fuss, and she slept deeply and regularly unless troubled by her teeth, some of which were then still coming through. The easiest way to soothe her was always to tell her a story, and her afternoon nap and evening bedtime were always prefaced by about half an hour of readings and recitations. This ritual became as central to my emotional wellbeing as it was that of my little sister, always a moment of perfect peace, the eye of my storm.

In happier days, my mother had owned the first volume of Kinder und Hausmärchen by the Brothers Grimm, and I recalled enough to improvise basic versions of the German folk tales I had heard in my youth, my favourite being ‘The Valiant Little Tailor,’ in which the hero tricks two evil giants into fighting each other. I could also offer fair renditions of ‘Cinderella,’ ‘Hansel and Gretel,’ ‘Little Red Cap,’ and ‘Snow White,’ and as all these things kept to a very precise structure it was a straightforward task to invent others. When I became bored with fairy tales, I would take to declaiming poems I had learned with my father, and on a good night he might even join in as I chanted lines from Scott, Coleridge, Byron, or Shelley while Sarah nestled in my arms like a kitten, calming me as I calmed her. We only had the one book, my father’s first edition of Lyrical Ballads, but I was determined to teach Sarah to read, so whatever story or verse was actually coming out of my mouth I had the book in my hand where she could see it, turning the pages regularly. She must have thought that slim volume to be the most magical book in the world, for its contents would have seemed to her infinite.

Seasoned knucks in quod will discourse at length on the horrors of incarceration; bewailing the mordant cold and the foul air within the cramped, overcrowded and filthy cells, gaol fever, the constant battle to cheat starvation, the rats, the rapes, the beatings— But the real torture is the boredom, all those frozen hours by which you measure out the passage of your life. The inmates of the Marshalsea were thus as aimless as apparitions, and they lingered in great numbers about the courtyard and the staircases, restless and miserable, for their cells were too hot or too cold, or too crowded or too lonely, and not a one of them really possessed the secret of knowing what the hell to do with all the time on their hands.

After we had been in residence some six months or so, one such wraith nervously appeared at our open door at the approximate hour of Sarah’s afternoon rest. Freddie was an orphan and only a couple of years older than I, although he acted as if he were younger, and appeared to have moved seamlessly from the workhouse to the debtor’s prison. I had not, at that point in my life, ever seen a more pathetic urchin; only the filth that encrusted him from his wild hair to his bare feet seemed to hold his bones together. He leaned unsteadily upon the heavy wooden frame and in a shy, soft and surprisingly polite voice he asked, ‘Might I sit quietly and hear the story?’ I had not the heart to send this broken boy away, so I beckoned him in and he positioned himself on the opposite side of the fireplace to my chair, crossing his spidery legs underneath himself.

Sarah was already upon my lap. She looked the boy over, sniffed like a puppy, and then returned her attention to the ubiquitous book. ‘Once upon a time,’ I began, ‘a little tailor was sitting at his table near the window—’ One story would take about five minutes to tell, and it usually took four or five to knock Sarah out enough to get her into her bed. I could then relax for the next hour or so. After the little tailor became king, Rapunzel had let down her hair, and the wolf’s belly was filled with rocks, I ended with a dash of Byron, carrying my drowsy charge to her cot while whispering the final lines, ‘A mind at peace with all below, a heart whose love is innocent.’

When I had finished and the child was down, Freddie rose without a word, and reaching into his rags withdrew a piece of greasy bread which he forced into my hands.

‘Thank you,’ he said in a whisper, before silently taking his leave.

‘What a strange boy,’ said my father.

Freddie returned the following day. Once more he spoke but little, other than to ask if he might listen, and to thank me when he rose to leave. This time he gave me some tea in a twist of newspaper. I urged him to keep it. ‘No,’ said he, cupping my hands in his own so I could not return the wrap, ‘I want you to have it.’ My father cleared his throat and told Freddie that we were very grateful. The young man let my hands drop, and looked not at me but somewhere past my right shoulder. I attempted to catch his eye but he looked away like a girl. ‘Same time tomorrow?’ he asked quietly.

‘Why not,’ said my father. I nodded in mute agreement and Freddie grinned back like an idiot. ‘What in God’s name is that child doing in here?’ he said when Freddie had taken his leave.

‘What are we doing in here? I said.

There was no answer to this, beyond the obvious, and my father did not reply. He shrugged and returned to his labours. I had chores to attend to, but instead I sunk back into my chair and could not move. To talk of the walls closing in would be a horrible cliché, and I will not use it (Lytton began Paul Clifford with, ‘It was a dark and stormy night,’ and has been rightly mocked for doing so ever since), but the room certainly became darker and more oppressive at that moment, and suddenly appeared to me flooded, the prison part of some vast submerged metropolis. The inner and outer worlds fused, as if I inhaled water that then froze, leaving me dead and buried in an ocean of ice. I could still see my father, though he appeared a great distance away. This had been happening to me more and more of late. I was caught in the grip of a monstrous and paralysing anxiety. While my body was useless my mind surged like a galvanic current. I was as a spirit trapped within its own rigid corpse, cursed to experience itself rotting to nothing with no possibility of either cure or oblivion. Then Sarah awoke. I rose without thinking to comfort her, and the attack passed.

The next day Freddie bought another gift of bread and a friend of about the same age that he introduced as Sid. ‘Well,’ said my father, ‘the more the merrier.’

I was far from sure about this new audience intruding upon my special time with Sarah, but in the Marshalsea you lived from meal to meal so I acquiesced. For her part, Sarah had no anxieties involving strangers; she enjoyed interacting with new people, so I decided to accept the extra scran and be grateful for it. We might be a novelty now, with our sweet little mouse and her gentile ways, but children soon grew and I had no desire to be beholden to the mercy of the dubsmen. Regardless of their kindness, they were still my gaolers, and I hated them accordingly. It also seemed to me that I was at least in some small way starting to earn my bread, while there was also an increasing sense of family about the place, Freddie and Sid beginning to occupy in my small world the roles of older but more artless siblings.

My not-quite-family now grew so fast you would have thought us Catholic, and within the month I was reading to a dozen or so children between the ages of about five and ten every afternoon, and receiving a penny a pop from the parents which Freddie dutifully collected and passed on. Then one day an older man knocked upon our door who was not a parent, and who had no clothes in need of repair.

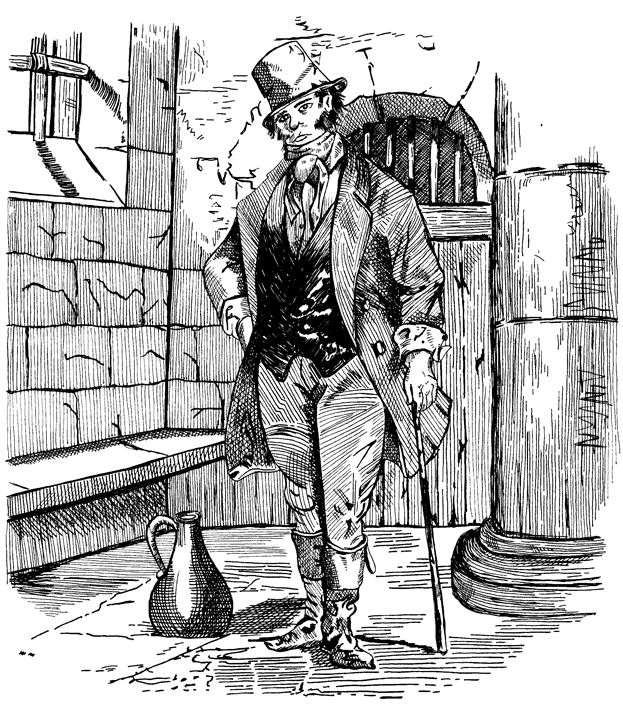

He introduced himself simply as ‘Bill.’ In common with most prisoners incarcerated for any length of time it was difficult to judge the man’s age; he might have been anywhere between thirty years old and fifty. Bill was not a small man, and a dilapidated top hat worn in mockery of better days gave him an extra eight inches or so, but he was still lost within a mouldy fustian coat obviously cut for a giant. He had the voice of working class London, born and raised, and a Cockney’s tendency to leer when he spoke. In round and rough tones, he explained that he had heard that I was a reader, and he was wondering if I might read a bit to him and his mates of an evening, for they knew not how to read themselves.

‘For a small remuneration, naturally,’ he growled.

I asked him what I might read, and he produced a small, fragile and coverless volume entitled The Lives of the Pirates, Being a True and Genuine Account of the Robberies and Exploits of Brigands, Buccaneers, Privateers, Corsairs, and Marine Freebooters from the Notorious Kidd and Teach who was also called Blackbeard to Long Ben Every the King of the Pirates & co.

‘It’s not Shakespeare, then?’ said my father, examining the book, his old sense of humour surfacing briefly, like a nervous goldfish.

He assented surprisingly quickly, though, declaring that he was all in favour of literature for the working man. It was agreed that I would read in the snuggery of a Sunday evening, after Sarah went down, for an initial fee of five pence per night raised by those there assembled, food and drink to be provided.

And that was how I became the Storyteller of the Marshalsea.

Click here to read Chapter IX

No Comments