In addition to reformers and evangelisers, another species from the outside well known to us was the tourist; dandies in the underworld who treated a visit to Bedlam, Newgate, or the Marshalsea as a social occasion.

Sometimes they would even turn up with hampers and make a day of it. And if prisoners were willing to be observed in their natural habitat then boons might be bestowed upon them, in the form of food, drink or money. My dad was apt to indulge the voyeuristic swine for the latter reason, playing the Father of the Marshalsea and then leaving it to their honour to tip him for an audience. If food were offered I would take it and hold my tongue, but inwardly I smouldered with a special kind of hatred reserved for the idle rich, those who viewed the lives of ordinary people as some form of entertainment (as long as we stayed out of their part of town), and had neither the wit nor the wisdom to realise that it was luck, not rank or birth, that separated them from us. They lorded it over the rest of us as if they had some God-given right to wealth, comfort and social superiority, when all they did was be born in the right place and the right time. It made as much sense to me as a man waking up on a fine, sunny morn and then taking credit for the weather. At least the evangelists and anthem quavers believed in something, no matter how implausible or misguided, and came to us to offer help, no matter how implausible or misguided.

I was in the snuggery one night, preparing for a recitation, when such a shower of bastards descended upon us. There were three of them, obviously blunted, that is in funds, wearing the flashiest toggery, and with their hair all faked in the newest twig. When the most rakish of the trio removed his tall silk hat, so powerful was the waft of macassar oil that it momentarily masked the common miasma of the room, that of sour sweat, smoke and strong drink.

‘Beautiful ladies,’ he intoned, addressing Nelly and her companion, a fading ginger known only as The Bat, so called because of her habit of only emerging in the dusk of the evening, and for the kind of suck she might offer when she slipped out her wooden teeth.

They simpered and giggled like drains, and the man took one in each arm and headed for the bar. His companions appeared older and younger than he. The younger looked embarrassed, the older good humouredly drunk. The regulars looked on in a collective and resentful silence, which allowed the older man’s voice to carry quite clearly across the entire room as he polished his tinted spectacles and addressed his youthful escort.

‘This is a fine sketch of real life,’ he was saying, in a rich Irish brogue. ‘Our good friend Tom is already sluicing his ivories with a brace of unfortunate heroines of the blue ruin, by the look of ’em.’ The man with the oiled hair, oozing over poor old Nelly and Batty, looked up and returned a lascivious leer. ‘Tom is in Tip Street upon this occasion,’ explained the older man, meaning that his friend was flush, ‘and the mollishers are all nutty upon him as you can plainly see, putting it about, one to another, that he is a well-breeched swell.’

‘Oi,’ said Nelly, ‘who are you calling a mollisher?’ This meant a prostitute in the vulgar tongue.

‘My dear lady,’ said the bespectacled man, cutting an exaggerated bow, ‘I assure you that I meant no offense.’ He called to his friend at the bar. ‘Tom, the lady is dry. Give her one from me, old man.’

‘Delighted,’ said the one called Tom, calling for a bottle of the good stuff. This seemed to mollify the mollishers, so the loud one carried on with his lecture.

‘This fine sluicery,’ said he, continuing to set the scene, ‘contains a rich bit of low life for our observations, my friend, and also points out the depravity of human nature. Feast your eyes upon them and rub off a little of the rust.’

The youth attended with exaggerated ear, for seeing life was apparently his goal, and this curious fellow with the shades was obviously playing Virgil to his Dante.

‘They are all resident within this grey bar hotel, my lad,’ counselled his guide, ‘for want of the blunt.’ The boy nodded in sage agreement, although whether or not he understood a single word in twenty was open to question. ‘And blunt, my dear boy,’ said the older man, pausing for theatrical effect, ‘in short what is it not?’ This was clearly a rhetorical question for he ploughed on without catching a breath. ‘It is everything now o’ days. To be able to flash the screens, sport the rhino, show the needful, post the pony, nap the rent, stump the pewter, tip the brads, and down with the dust, is to be once good, great, handsome, accomplished, and everything that’s desirable. Money! Money is your universal God, and these poor folk are fallen angels.’

He put that quite well, I thought.

‘They are down,’ said the oratorical bellowser, who was obviously building up to a big finish, ‘they are out, but they are, my dear boy, inevitably, invariably, indubitably life in London!’

‘Hear! Hear!’ shouted Tom from the bar, while Nelly beamed desperately and The Bat sucked at her glass like a piglet at a sow’s tit. ‘I am quite satisfied in my mind,’ he began, ‘that it is the lower orders of society who really enjoy themselves—’

I had heard enough, and my time around Bill and his boys had given me the mettle to back up my simmering indignation. I rose to my feet and bellowed across the room. ‘Oh shut your fucking bone box, you sack of shit!’ said I, approaching the one called Tom. He closed his hole in shock, as if suddenly slapped, but the colour quit his face in silent fury.

‘Such a parade of mediocrity,’ I continued, ‘such a cavalcade of nothing!’ There was a murmur of approval around the room, although Nelly was glaring at me, for she was a forward girl, a Quicunque Vult as they say, and ever ready to oblige whosoever wished it. ‘Are we to be observed for sport,’ I said, appealing to my fellow inmates, ‘like the poor mad fools of Bedlam, by this bloody bingo club?’ I turned my aggressive attention to each in turn, starting with the bantling chav: ‘A quockerwodger in rank bounce,’ (I indicated that I was referring to the young man with a loud sniff, then I directed my gaze towards the Irishman), ‘a bog trotting cheesecake steamer, and, most importantly,’ I continued, looking Tom clear in the eye, ‘a beau-nasty, woolly bird’s beard splitter like this.’

He rose from his stool with his fists clenched and murder in his eyes. His nose, hooked and prominent, gave his long face a raptor-like appearance. I was far from sure I could take him.

‘Do you dare—?’ he began, before he was interrupted again, all-a-mort, this time by the Irishman, who was slowly applauding.

‘Bravo, sir,’ said he, coming over and clapping me on the shoulder like a long lost friend. ‘Well said, my dear young fellow, you patter the Flash like a family man.’

‘On occasion,’ I said, caught on the back foot by this unexpected amicability.

‘You are perverted by language, my young friend,’ he said, with something like respect.

‘As, sir, are you,’ I replied. He beamed widely in return. It was very difficult not to immediately like the man.

‘And what, may I ask,’ said he, ‘did you just call my friend?’

‘A slovenly fop who prefers to shag sheep,’ I said, translating casually.

Tom again erupted, and his two friends were forced, with some difficulty, to hold him onto his stool.

‘’Tis like trying to keep a dog in a bath,’ observed the Irishman.

‘I bet that’s what you say to all the boys,’ said a rich, cloying voice from the rear of the room. The trio stopped playing with themselves, and turned toward the speaker.

‘My God,’ said the young one, in an awed whisper, ‘what a fabulous voice.’ The speaker remained in the shadows, but I knew exactly who it was.

I was not alone. ‘As I live and breathe,’ said the Irishman, ‘would that be Flashy Nanse of All Max?’[7] He turned to his young charge. ‘You are privileged to witness a living legend, for this one has gammoned more seamen out of their vills and power than the ingenuity or palaver of twenty of the most knowing of the frail sisterhood could effect.’

Tom was likewise enchanted. Perhaps he and I had something in common after all. ‘Give us a touch girl,’ he said, advancing towards her, Nelly and Batty forgotten in an instant, ‘for old time’s sake.’

A naked blade flashed through the air in reply, and embedded itself at his feet.

‘You come near me, Corinthian Tom,’ said Nanse, ‘and I’ll cut it off.’

The Irishman roared with laughter, removing the stiletto from the floor and handing it back to its rightful owner. ‘Not since the days of Wilhelmina the Werewolf Woman,’ said he, ‘have the concepts of pain and pleasure been so beautifully entwined.’

At these words I was thrown into a state of confused agitation. Everyone was laughing now, even Corinthian Tom, but for me the floor was pitching and reeling like a deck plate in a gale. I wanted to sit down. ‘How did you know about Wilhelmina the Werewolf Woman?’ I managed at last, choked and panicking.

‘My dear sir,’ said the Irishmen, ‘they are bringing her out in half the theatres in London.’

I knew not whether to laugh or cry. Ainsworth had obviously found a publisher, but this was the first I had heard of it, being stuck in here like a dog.

‘But I wrote that,’ I whispered, crestfallen, ‘it’s mine.’

The Irishman wrapped a brawny arm around my shoulder and blasted me with his beery breath. ‘Then we must have you,’ he said.

‘Avast and belay,’ said Tom, coming over, ‘this one’s a liar and a scroof, plain and simple. He’s half-flash and half-foolish, and good for nothing but the sea lawyers I’ll be bound.’

‘Nonsense,’ said the Irishman, with clear authority, ‘this young man is a quill driver and a brother, and that’s as plain as the formidable nose upon your face.’

‘I’ll not support it,’ said Tom.

‘Noted, but overruled,’ said the Irishman, pulling out a huge watch upon a heavy fob. ‘Now,’ he continued, ‘unless we wish to spend the night in this charming place, I suggest we go to the bolt-in-tun.’

Tom responded by taking Nelly in his arms, sweeping her off her feet and kissing her deeply. The Bat, meanwhile, surreptitiously removed the bottle they had been sharing, as, unlike her friend, she could see that the bit of a spree was obviously at an end, at least as far as these ladies were concerned. ‘Parting is such sweet sorrow,’ he said, before dropping her on her arse and taking his leave, laughing.

As he reached the door, Nelly, looking flushed and breathing heavily, addressed him from the floor with a most unfeminine imprecation.

‘Madam, I am shocked,’ said Tom, in pantomimic horror. He shoved the young man through the door in front of him, and then followed him into the courtyard, leaving only the grand orator in the room.

‘Do you feel that, my young friend?’ the Irishman called to me with a gleam in his eye. ‘The dice are rolling.’ The trio then left, singing ‘Come list ye all ye fighting Gills,’ a popular boxing song back then.

I fell into a seat next to Nanse. Bill was not in evidence. ‘What just happened?’ I asked her.

‘Something bad,’ she said, looking balefully towards the door. ‘Why the Christ did I make myself known to them?’

‘I thought you were helping me,’ I said.

She looked surprised. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘I suppose I was.’

We had, I later gathered, been blessed with a visit by the predatory rake Corinthian Tom Hawthorne, his country cousin Jerry, and their mate and mentor Bob Logic, a cheerful middle-aged scholar with a razor-sharp wit and a taste for wine and women, who everybody knew were, in reality, the brother artists George and Robert Cruikshank, and the journalist Pierce Egan. These silly sods were regulars of the Fancy, the finishes, the penny gaffs, barrel houses and brothels of the East End. Egan published their supposedly fictional adventures every week under the title of Life in London. Nanse said she reckoned their true identities were the worst kept secret in the city.

‘How do you know them?’ I asked her carefully.

‘From bitter experience,’ said she. ‘Egan means well, but don’t trust that Cruikshank further than you could shoot shit from your hopper.’ I assured her that if our paths ever crossed again I most certainly would not. She let the matter rest at that, and left soon after. ‘I need to find Bill,’ was all she said, distractedly, when I attempted to kiss her goodnight. ‘If that old fool writes that he saw me here then the jig’s up for sure,’ she added cryptically, ‘and if the jig’s up with me, it might be up with a good many more besides.’ Then she was gone. There was no invitation to her room that night, and I retired miserable, confused, and alone.

I saw little of her after that night, and a couple of days later, without a word, she was gone. The word was that all claims against Bill, Nanse and Sid had suddenly been dropped, and they had left on Wednesday morning as soon as the great gate was opened. The feeble minded boy Freddie and I were left to mourn their absence together. I was bereft on a level I had not experienced since the death of my poor mother. I cared for my sister in a daze, reacting to the most minor domestic demands and calamities with disproportionate fits of rage or despair. I slept not, haunted by the image of my lover.

So, it would seem, was Freddie. By and by, his story came out. ‘She was nice to me, too,’ he confessed, fidgeting, ‘until she got bored.’

‘How do you mean “nice”?’ I asked, with an increasing sense of unease. Was she kind? Did she feed him? Did she take care of him? Why did that guileless adjective, even on such childish lips, sound so lascivious?

He hugged himself, and grotesquely mimed the act of kissing. ‘You know,’ he said, ‘nice.’

‘Was she nice to Sid, too?’

‘Oh yes, sometimes at the same time as she was being nice to me.’ I had heard enough, but the idiot kept talking. ‘She wasn’t so nice after you came along,’ said he, ‘not very often anyhow.’

‘Did Bill know?’

‘Oh yes, he liked to watch. Sometimes he’d be nice too.’ He looked at me pleadingly then, and I presumed that his simple mind was relieved to have shared its burden. I was wrong. ‘Perhaps,’ he said, reaching tentatively towards me, ‘we could be nice to each other instead.’

‘Jesus Christ, Freddie!’ I avoided his hand like a wasp. I had not the heart to hurt him though, so I added, ‘Let’s just be mates, same as ever.’

‘Same as ever,’ he said, with an asinine grin.

What could I do? We were both of us victims of the same crime, after all, although I knew I was not so innocent as he. Had she appeared again at that moment I would still have followed her to the place where the worm never dies and the fire is never quenched just for one more touch.

David had more concrete intelligence. I knew he would. Nanse, he had discovered, was a ‘hempen widow,’ that is her husband had been hanged, while Bill was an ‘area diver,’ a housebreaker, and Sid, who was presumed to be Bill’s son, was a ‘buzgloak,’ or pickpocket, and sometimes also a ‘standing budge,’ meaning he would act as a scout or spy for thieves. The three of them formed part of a notorious crew from Saffron Hill, who had been boned the previous year. Bill had contrived to hide in plain sight, and had bribed some associates to take the role of creditors and have the ‘family’ incarcerated for entirely fictitious debts until the whole affair blew over. Egan’s identification of Nancy, if publicised, would therefore be fatal, at least for her men folk, for both were wanted for capital crimes. With the game likely up, Bill had got word to his counterfeit creditors, and they had immediately affected to waive all monies owing. Freddie, it would appear, was not of this gang, and had been picked up for a bit of sport and easily discarded, as had I.

‘How do you know all this?’ I asked him.

‘People talk,’ he said, casually citing the simple credo of the born journalist. He saw right through me as well, even then, and even though I had told him nothing of my relationship with Nancy. ‘Chin up, Jack,’ he said, ‘you still have me.’

That was not true, but it was kind of him to say so. Something turned up not long after. His father came into some money and the family were released. David promised to visit, but I assumed after a while that his parents forbade this, because he never came.

*

I now hungered for release, with a passion I had not felt since resigning myself to an endless incarceration. Time froze, creeping down the walls like the black mould mottling the plaster about the skylight in my cell. If only I could get out, I thought, then I could find her. I was sure that in the end I had meant more to her than the others, and that some expressions of love could not be easily forged, even on the lips of one as artful as her.

I now hungered for release, with a passion I had not felt since resigning myself to an endless incarceration. Time froze, creeping down the walls like the black mould mottling the plaster about the skylight in my cell. If only I could get out, I thought, then I could find her. I was sure that in the end I had meant more to her than the others, and that some expressions of love could not be easily forged, even on the lips of one as artful as her.

Having no other role, I continued to read in the snuggery. I dallied briefly with Nelly, but it wasn’t the same. She was a miserable cow, and she always charged, and without Bill to act as my agent I made much less from my readings. The Bat would have popped her teeth out for a large gin, but just as Buckingham drew the line at the murder of the princes in the tower even I had my boundaries.

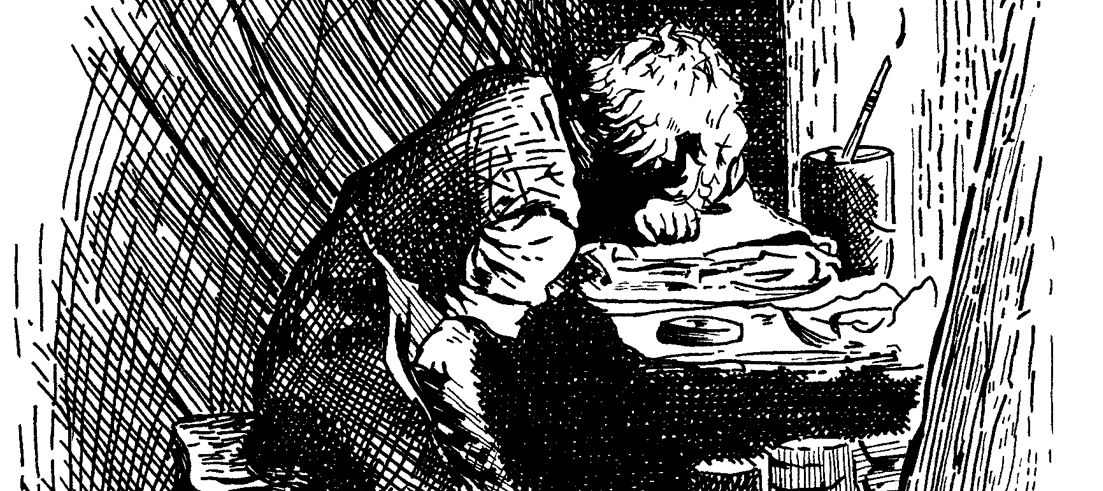

I had stopped writing my own material, for my heart was no longer in it now that my work was stolen and my muse had taken flight. Instead I relied largely on broadsheets and papers discarded by visitors and diligently collected by Freddie. He could not read, so could not assess the content and quality of the literature he procured, but he did his best. In return for his labour my father and I allowed him to reside in our room, where he also proved to be invaluable in the care of little Sarah.

In the snuggery, the crowd-pleasers remained accounts of crime and retribution. The prisoners, unable to enjoy a good hanging themselves, were reduced to consuming their pleasures vicariously through the medium of print. I personally found the contemporary reports to be much less fun than the Newgate Calendars, which rendered pirates and highwaymen romantic, while the distance of centuries made their last ends noble and historic, rather than uncomfortably real. Reading the last words of children publically executed the week before for stealing food appalled me. But the law was vindictive, cowardly, mean spirited and ignorant, and cared not for my opinion.

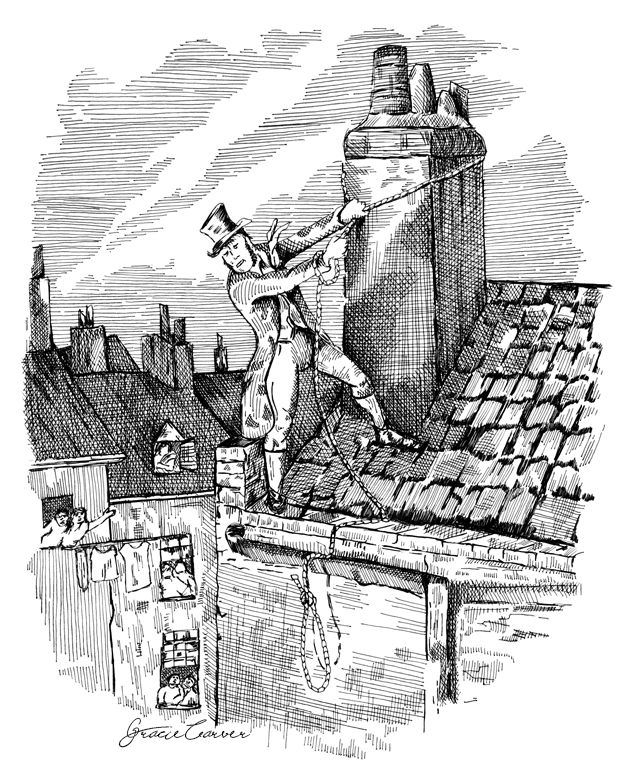

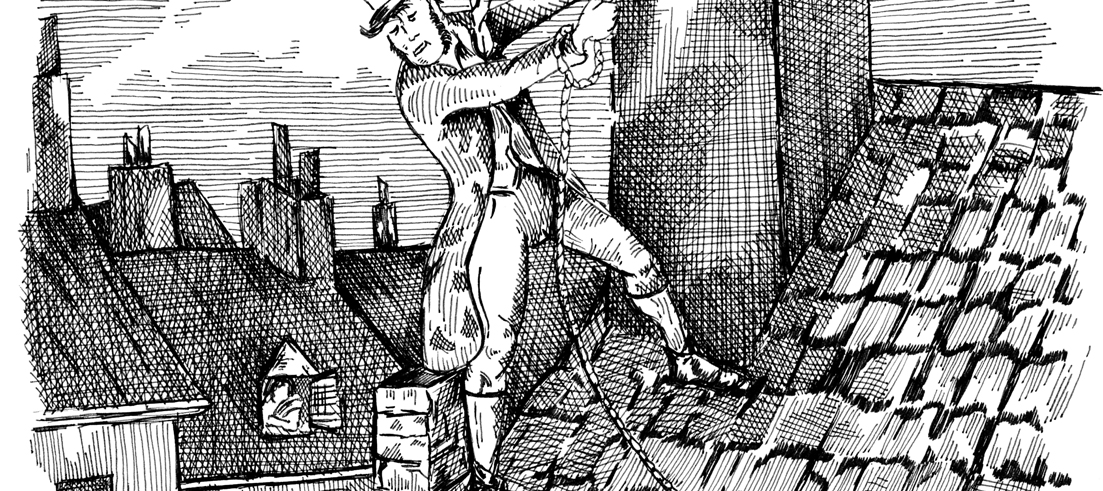

Freddie could not be blamed for the last broadsheet I read out in the snuggery. He had no idea what it said, while I was in a hurry to get it over with when he pressed it into my hand, and more than a little pissed. It was a classic study in scarlet, topped by two woodcut illustrations. The first depicted a rough, wild-eyed man cudgelling a woman at his feet, her hands raised as if in prayer; the second was of the same man decapitated at the end of a rope, his spurting corpse falling from the roof of an unkempt building into a crowd of horrified spectators. The headline read ‘Horrible Murder and Accidental Suicide in Saffron Hill!’

One William Sikes (or Sykes), I read, had beaten his sui juris wife to death in a rented room, for reasons that remained unclear to the authorities. He had then tried to escape across the rooftops after a young man, believed to be his son, raised the alarm. The murderer was attempting to swing from one building to another by means of a rope around a chimney stack, when he lost his footing and accidently hanged himself. As hanging, the article explained, was an exact science by which the length of the drop must be calculated according to the weight of the condemned, Sikes’ impromptu self-execution had taken his head clean off. The couple were part of a local gang of housebreakers and pickpockets that had been broken up the previous year, and were believed by police to have left the city. The son was suspected of acting as an accomplice in several robberies and was on remand in Newgate. The murdered woman, I read, was a well-known local prostitute known as Nancy or Flashy Nanse.

A deathly silence descended upon the room. I stared numbly at the document in my hand, noticing as if in a dream that Freddie had slumped down in a corner and was quietly weeping. ‘Well, fuck me,’ said Nelly, finally.

Still, no one else uttered a word. Was this, then, I wondered, the only epitaph my first love deserved? I dare not speak, for fear that the grief that now congested my soul would surge out of my mouth in a wailing lamentation that I would be unable to contain. I wanted to claw at my flesh, rip my own teeth from my jaw, and slam my head into a wall. I wanted to be dead, too. I didn’t know what I wanted. Finally, I stopped looking at the broadsheet.

It was Bertie the Badger that broke the silence. He stood slowly and raised his glass with great solemnity. ‘Bill and Nanse,’ he said.

‘Bill and Nanse,’ agreed the regulars, lifting their glasses in turn.

‘May they sleep well,’ said Bertie, his voice faltering.

He drained his glass and rushed from the room. The crowd closed in his wake and began once more to drink and talk. Someone, the barman I think, given the generosity of the measure, shoved a half pint glass of neat gin into my trembling hand, and I drained the burning bastard in a single draught, before following Bertie out of the room. For all the good it did me it might as well have been water.

I passed the night on the stairs that had led to her room, which was now occupied by a stranger, self-murder on my mind. But I had not the nerve, and still do not, although the comforting thought of suicide has since carried me through many another bad night. Having nowhere else to go, I eventually returned to my cell, and mechanically began my morning ritual. There was no sign of Freddie, who had likely drunk himself into oblivion in the snuggery.

Sarah was already awake and talking about Carol and dogs. I tried to interact with her as best I could, but my mind kept returning to memories of my lover, the image of the woman in the picture, and the terror and pain of her final moments. I thought of the death of Bill, too, and wished his immortal essence well on its final journey, because I do pray for the souls of my enemies. I pray they go to Hell.

‘Doggie!’ said Sarah from her cot.

‘There’s no dog, darling,’ I whispered, attempting to start a fire. The smoke made my eyes smart and I sniffed violently.

‘You ill or something?’ said my father, rising from his bed.

‘I just heard Bill and Nanse died,’ I said, knowing that the intelligence would mean little to him. When they had left he had not disguised his delight at the removal of their influence.

He was gentle enough to ask what had happened, but all he could say by way of reply was that they had brought it upon themselves. I felt my blood begin to boil. I realised that I wanted a fight, so I turned on him with a low growl, poised to pounce and just then more animal than man.

‘You sanctimonious cunt,’ I rasped through clenched teeth, aping Bill at his most ferocious. This had the desired effect. My father backed away.

He did not, for all that, have the good sense to hold his tongue.

‘She was a whore, son,’ he said quietly, ‘and twice as old as you at least,’ as if the latter point was somehow worse than the former.

‘I don’t care,’ I said, trembling with rage, ‘I loved her.’

And however idiotic, self-destructive, shameful or downright absurd that statement must have sounded to him, what I needed at that moment was his love, his sympathy, and his support. If my son ever comes to me with such a grieving heart, no matter how inwardly relieved I might be that his latest mistake has now been rectified, I will give him that love without question.

But my father was no longer that way inclined, at least not to me. ‘You won’t believe me now,’ he said, ‘but this is the best thing that could have happened.’

‘But she’s dead, Dad.’

‘Good,’ he said, at which point I swung for him. It was an inexpert punch, a glancing blow at best, but I could see in his horrified eyes that I had done more damage than any prize fighter could have.

‘Doggie,’ said Sarah emphatically.

‘There’s no fucking dog!’ I bellowed, turning my fury on her. She looked shocked, and then began to cry.

‘Get out,’ said my father, in a voice that suggested to me that he meant it, but should I refuse he was unsure as to whether or not he could enforce the injunction.

‘Doggie!’ my sister again repeated. This time I looked. There was a huge rat nestling in the corner of her cot, the kind you normally only see in graveyards. ‘Doggie, doggie, doggie,’ said Sarah, prodding at the hideous thing with her tiny hand.

In the time it took me to get to her, the monster had already struck. Sarah screamed and withdrew her ruined hand, her blood splashing across the wall. The rat sprang from the cot and disappeared under my father’s bed. I ignored it and grabbed my sister, examining the damage while my father got in the way.

It could have been worse, I suppose, but the brute had taken off the top joint of her right index finger. And she had possessed such beautiful hands. She sobbed and shrieked as I wrapped her hand in a sheet to staunch the bleeding. I had no idea what to do, so I just held her as she screamed. Eventually it occurred to me that we might distract her, so I placed a heel of dry bread in her good hand and she began to gnaw at it. In want of anything useful to do, my father searched the room in vain for the rat, until I managed to convince him to go to the lodge and request a doctor be sent for. I gave him all the money I had for this purpose.

‘This is all your fault,’ he said, as he left the room, and he was right.

We spoke little upon his return, by which point Sarah had fallen into a deep sleep. I marvelled at her resilience. She could, so it seemed, bear the loss of a finger bravely, whereas if I ever sneezed loudly in her presence she would scream and sob as if tortured.

The sawbones arrived in the early part of the afternoon, accompanied by the head turnkey and a sour-faced man I did not recognise. The latter pair kept to themselves while the doctor attended to Sarah. He told me to keep the hand clean and apply an ointment that smelled of paraffin each time I changed the dressing. For this foul concoction, a bandage and his learned opinion he charged us a guinea and took his leave, assuring us that sleep was nature’s balm and that there was little harm done, a diagnosis I did not share given that my perfect sister was now scarred for life.

The man of mystery now stepped forward, removing his hat and absentmindedly rubbing his head, which was as bare and pitted as a gunstone ball. ‘Mr. Vincent,’ he said, in a voice that was authoritarian yet oddly common, ‘I am here by order of the court to inform you that your debt has been paid in full. You are free to go.’

My father leapt up and grabbed the stranger’s hand, shaking it furiously.

The man looked ill at ease, and regained possession of his hand firmly. He looked at the turnkey appealingly.

‘He doesn’t mean you, Joseph,’ said the gaoler quietly. ‘He means Jack.’ The colour drained from my father’s face like the blood leaving a butchered pig. He swore violently.

‘There’s no need for profanity,’ said the stranger.

‘He’s right, Joe,’ said the turnkey, ‘this is good news, surely.’

I said nothing. If I had any more news that day, of any colour, I did not think I would be able to stand it. At that moment, though, I would have done anything to exchange places with my father. I was past caring now, but the humiliation and disappointment on his face was truly terrible to behold. I wanted to go to him, but was too ashamed at my own good fortune to make such a feeble gesture. It was clear that that brief moment of hope had cost him more than the years of despair. He looked at me then, with a darkness in his eyes that has haunted me ever since. It was an expression of pure hatred.

‘Take him,’ he said flatly, addressing the two men before turning his attention to me. ‘Collect your belongings,’ he instructed me coldly, ‘and get out.’

‘Dad—’ I pleaded, uselessly.

‘Get out,’ he said levelly, in a voice I did not know. ‘Get out, and don’t you dare to ever come back.’

‘Joseph—’ the turnkey began, but the desolation written upon the face of my father strangled his appeal at its birth. ‘I’ll leave you to your business, then,’ he finally said, before beating a hasty retreat, closely followed by the clerk of the courts.

I had nothing to collect save the clothes I stood up in, and a destroyed bible containing between its covers the loose leafs of my incomplete serial. My father’s Lyrical Ballads, my magic book, stood on top of this profane manuscript, and I took that too, for he had turned his back on me and saw not what I did. Sarah still slept, so I left without saying goodbye.

I next sought out Freddie, who was sleeping like a dog before the embers of the fire in the snuggery. I shook him awake, and, with a terrible weight upon my heart, I explained that I too must leave him. It was a miserable farewell, for he wept and said that I was the last true friend that he had, and that like Bill, Sid and Nanse he knew he’d not see me again.

‘That’s not true,’ I pleaded, taking his hands in my own and looking him firmly in the eye. ‘You stay close to Dad and Sarah and take care of them for me, for we are all family now.’ He wiped the snot from his nose with his sleeve and nodded enthusiastically. ‘And I swear,’ said I, ‘that somehow I will find a way to get you all out of here.’

We embraced then, and I left without another word. I had not a penny to my name and nowhere to go. I made no further farewells, and trudged towards the gate and the alien city beyond with no more idea of what was to happen than I did regarding my stalled and unfinished serial. When Nanse left and I stopped writing, my hero was walking the plank in shark infested waters and anticipating Valhalla on the noon tide. It occurred to me that we had an allegorically common dilemma, in the manner of the oriental story about the tiger, the cliff, and the strawberry. I could no more retreat than could my hero, and the city, from what I had heard of it, consumed the likes of me in a single bite. As far as I could see we were both buggered, but with revenant pirates at his back, vicious fish beneath, and not a strawberry in sight, I suddenly heard his voice in my head (which is always the sign of a good character).

‘Any man that fears the unknown,’ said he, ‘will one day take fright at his own arsehole.’

The fact that he was a figment of my imagination notwithstanding, he had a point. I made a mental note to use this line somewhere, took a deep, purifying breath, and struck out for the city.

Click here to read Chapter XIII

No Comments