My mysterious benefactor had, of course, been Egan; Bob bloody Logic himself. Having built up all my courage to walk through that Plutonian gate and face the Modern Babylon on my own, he was waiting for me across the street, learning against a knacker’s wall and smoking a long cheroot.

‘Well if it isn’t London’s latest literary sensation,’ he said, revealing both rows of his glittering teeth in a broad grin, and thereby saving me from the indignity of offering myself up to the mercy of my uncle, which had been the only plan I had thus far formulated.

I did not know it then, but he had recently left the Weekly Dispatch to publish his own Sunday newspaper, Pierce Egan’s Life in London and Sporting Guide, and he was desperate for cheap copy. I was tailor-made for his needs. My apprenticeship in the Marshalsea had made me, in his words, ‘street wise,’ while ‘Wilhelmina’ had proved that I could write, and for peanuts at that.

I offered him my hand and said no more than, ‘Thank you.’ He wrapped his arm about my shoulder and gently led me away. I have not returned since, and ten years ago the damned place was finally closed by Act of Parliament. They call it Angel Court now.

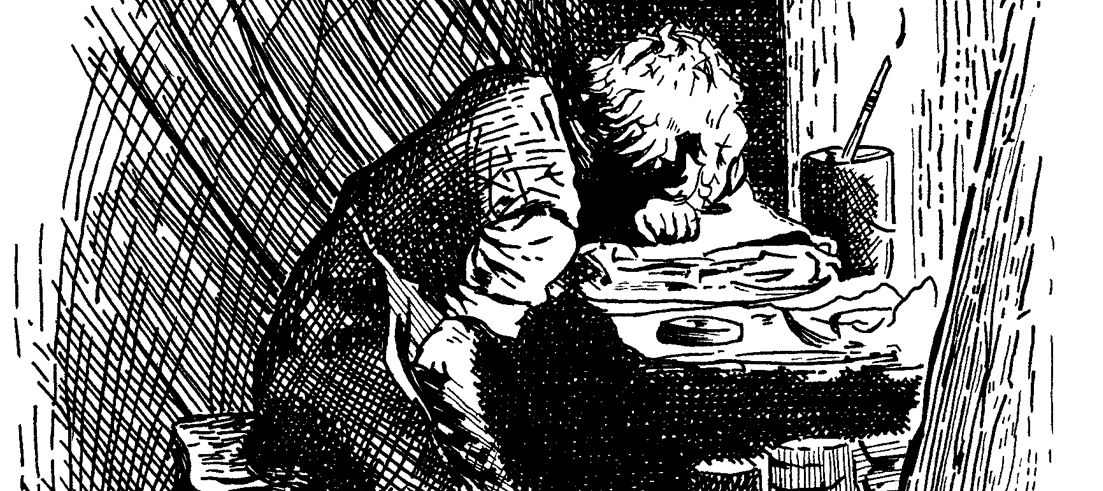

Like most writers, Egan did not shut up. His idea of conversation was to monologue in the manner of Socrates, leaving one only the space to occasionally affirm or deny before he launched into a new topic. He would only pause if something struck him as worth recording, in which case a small moleskin notebook would appear in his hand, into which he scratched hieroglyphics with a stub of pencil.

‘Shorthand,’ he explained, ‘invaluable in our line of work. I can teach you, if you’ve a mind to learn.’ I assured him that I was most eager to do so, and he took me at my word and over the next few months pretty much taught me everything that I know about journalism, although not, as he was fond of saying, everything he knew.

‘Well,’ said Cruikshank, when next we met, ‘you cannot legislate against wrongful encouragement.’

On that first day I learned two important things. The first was that Egan had not paid my debts, merely acted as my agent with Ainsworth (who was now relocated to London), and obtained my ten bob for ‘Wilhelmina,’ which had now made several publishers and theatricals rich through unlicensed adaptation. Ainsworth had not done too badly either, and whereas those that had knocked off the story were under no legal obligation to me whatsoever, Ainsworth, with whom I had a contract that he had discharged to the letter, was decent enough to also offer me a share of his profits. Egan had used this to pay my debt in full, and after a modest deduction for expenses he passed the balance onto me. It was a couple of shillings shy of ten pounds, which was a small fortune in those days, and easily enough to live well off for a year. It could have also made a modest yet significant dent in my father’s debts.

‘You are returned to your rightful station in the world, my young friend,’ said Egan, ‘now come and write for me!’ Under the circumstances, this was hardly an offer I could refuse. His enthusiasm, like his long laugh, was also infectious. After half an hour in his company I was convinced his newspaper would shortly be bigger than the Times.

The other thing I learned that day was my new employer’s philosophy of what is nowadays called social investigation, and which I was expected to assimilate and apply. ‘The Metropolis,’ he liked to say, ‘is a complete cyclopædia, where every man of the most religious or moral habits, attached to any sect, may find something to please his palate, regulate his taste, suit his pocket, enlarge his mind, and make him happy and comfortable!’

I caught on straight away. This was what David and I had been trying to do with our childish character studies, and was also obviously what had brought Egan to the Marshalsea in the first place. ‘And it is our job,’ I conjectured, ‘to read the city, and report upon it.’

‘Exactly so,’ said he, ‘for there is not a street also in London, but what may be compared to a large or small volume of intelligence, abounding with anecdote, incident, and peculiarities. A court or alley must be obscure indeed, if it does not afford some remarks, and even the poorest cellar contains some trait or other, in unison with the manners and feelings of this great city, that may be put down in the note book, reviewed at an after period, and then reported for the edification, pleasure and satisfaction of our readership.’ This he called ‘seeing life,’ which, he noted, was what his readers also wished to do, but without being seen themselves.

‘But I don’t know London,’ I conceded.

‘I know,’ said he, smirking like a slightly unhinged ten-year-old, ‘isn’t it wonderful?’

And thus began my rambles and sprees through the metropolis, my very own rake’s progress. This was exactly what I needed, or so I thought, to drown out all the memories that were trying so aggressively to drown me. If I stopped moving, watching, writing, and drinking, even for a moment, they would rise up from the depths to consume me.

I fought hard to control and conceal these dangerous emotions in public, while affecting a devil-may-care attitude which I largely copied from the more confident Cruikshank, George, who paradoxically turned out to be the younger brother. You would not have thought so to look at the pair together: Bob fresh faced and innocent, George debased, decadent and debauched. Inwardly, I perversely longed for my former life in the Marshalsea, another home to which I knew I could never return, for the people that had made it so were either gone, against me or dead. I believed myself abandoned by my young friend from the Hungerford Steps, despite all the support I had given so freely; I was betrayed by my father, while towards Sarah and Freddie I felt a crippling sense of guilt. Nanse I loved as much as I hated. I was furious with her for using me, leaving me, and, most of all, for dying, the silly bitch. Worst of all, my father’s parting words would not leave me: This is all your fault.

But unlike Egan I was no left-footer. There was no absolution available to me, only the endless derangement of the senses that my new job afforded me, for Egan had made me his apprentice in all things, including the Irish custom of drinking oneself blind every night.

These were still the times of the bucks, blades, bloods and bruisers. I did not know it then, but I was in at the death of that era. George IV was still on the throne, and London in those days was a colourful and dynamic place to be, the throbbing heart of a country intoxicated with victory and basking in the afterglow of Waterloo. Boroughs were expanding, the population was in flux, and although no longer quite the bawdy Augustan pantomime chronicled by Boswell, the capital was far from the puritanical Pandemonium presently presided over by that sanctimonious cow, Victoria. Industry, trade and sobriety were not yet in fashion, and in the fast set to which I now belonged, idling, gaming, drinking and whoring were the sport in view. Corinthians, plungers and dandies were still abroad most nights, staking their fortunes on the turn of a card in the hells around Hanover Square, drinking cross-ways in the clubs of St. James’, wrecking the wenches of Waterloo and Piccadilly and then slumming it in the brothels and gin palaces of the East End.

‘It is never too late,’ Egan would say, ‘to have a happy childhood.’

I confess that it is all a bit of a blur now, but then the articles remember that period for me, although the so-called ‘Victorians’ burn Life in London nowadays, alongside Mrs. Wilson’s memoirs. I still have copies of both, however, along with some of my own memories of Mrs. Wilson, whose favours I once shared, though they never knew it, with the Prince of Wales, the Lord Chancellor, the Governor of the Bank of England, and four future Prime Ministers.[8]

I had quickly revised my opinion of the present company. George Cruikshank took some winning over. He had a fast temper and never forgot a slight; he was also fiercely possessive of his friendship with Egan. I got on his good side by deferring to him in all things pertaining to the life of the city. He loved to lead and guide, and already his brother was tiring of this and straining at the leash. I therefore assumed the role of ‘Jerry’ when Robert was otherwise engaged and let Cruikshank act as my mentor just as much as Egan, the latter in journalism, the former in hell-raising. Cruikshank was a true Corinthian back then, although you would not think it these days, with all his fine preaching on abstinence and temperance (while everyone knows he keeps a mistress and a small army of bastards hidden in Hampstead).[9] It was also an easy matter to flatter his illustrative skills, which were, and remain, stunning. Egan had it right when he called him ‘the Gillray of the day.’ Nowadays he is more like Hogarth, an even better graphic artist, but more puritanical and much less funny.

Egan, then about fifty, was more of a kindred spirit, being the son of an Irish road-mender who, like me, had received little formal education. He became a printer’s apprentice at the age of twelve, acquiring a love of the written word and a flair for linguistic experimentalism that I have never since seen matched. Also like me, he had soaked himself in English literature, as well as some more popular sources, such as broadsheets, Newgate calendars and gothic romances. Upon completion of his apprenticeship, at about the same age as I was now (sixteen), he had thus entered the cut-throat world of popular printing, publishing and bookselling, starting out as a copy-editor and proof-reader, but quickly advancing to hack writer and catchpenny broadsheet-monger. Not exactly Jane Austen, our Bob Logic, but he was widely read and he made money.

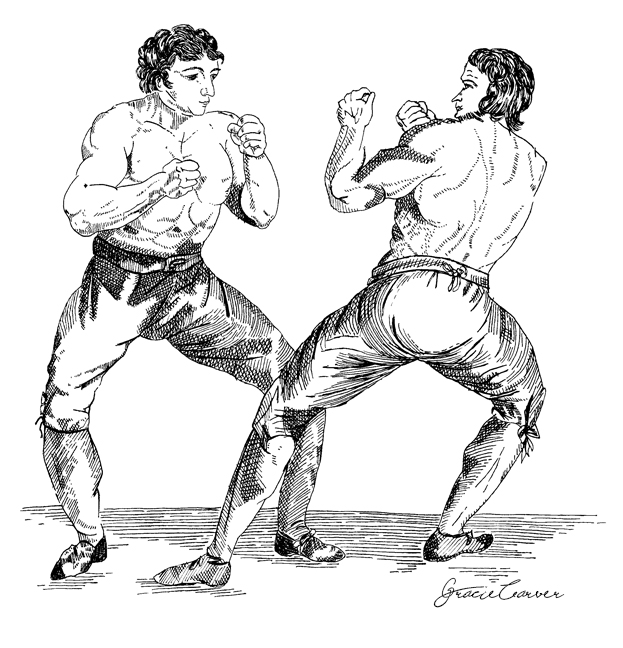

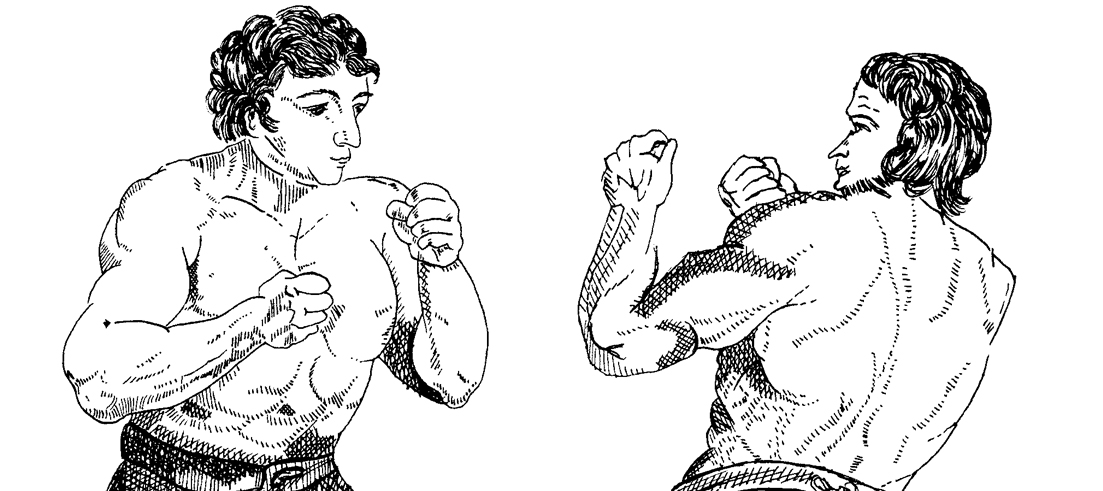

After the war he crossed over into sporting journalism for the Weekly Despatch, covering the Turf and the Chase, and, most importantly, the Prize Ring, or ‘Fancy,’ illegal bare-knuckle boxing matches that could last for dozens of irregularly timed rounds. His serial Boxiana or Sketches of Ancient and Modern Pugilism was still running when we met, and I was expected to assist by covering bouts he was unable to attend. The ‘Sweet Science,’ as he called it, was his passion, and the Fancy the temple in which he came to worship, presenting this insane milling house to me as something magical and sacred, although it scared the hell out of me.

After the war he crossed over into sporting journalism for the Weekly Despatch, covering the Turf and the Chase, and, most importantly, the Prize Ring, or ‘Fancy,’ illegal bare-knuckle boxing matches that could last for dozens of irregularly timed rounds. His serial Boxiana or Sketches of Ancient and Modern Pugilism was still running when we met, and I was expected to assist by covering bouts he was unable to attend. The ‘Sweet Science,’ as he called it, was his passion, and the Fancy the temple in which he came to worship, presenting this insane milling house to me as something magical and sacred, although it scared the hell out of me.

By hanging around with the clientele—working men, gypsies, whores, swells, half-swells, nib sprigs and tidy ones, hard cases, head cases, drag fiddlers, bookies, buggers, bucks, bloods and thieves—I was gaining a knowledge of the London underworld that would serve me very well for several years to come, until the New Age dawned and it was no longer good to be bad. (The scales had fallen from my eyes by then in any event.) I was also rubbing shoulders ringside with quality. Courtiers, courtesans, and plungers (army officers who had purchased their commissions and never left London or fired a shot in anger) gamed and drank with dandies and Corinthians. It was rumoured that the King himself sometimes still attended a bout in disguise, as he had done when Prince Regent. To Egan and Cruikshank, the so-called ‘Canting Crew,’ the truly terrifying villains that not only patronised but ran the Prize Ring, were not representative of the collectively menacing underclass that already so troubled politicians, but characters to be cultivated, and with whom one might have a bit of a spree. It was, however, notable that the honest poor interested them but little.

I was accepted into this fraternity surprisingly quickly, on account of Egan letting slip to the right people that I had ‘worked for Bill and Nancy, late of Saffron Hill.’ I confess that I found this quite upsetting at first, but this reputation was certainly the passport I required, for although Egan was evidently regarded with great affection by the followers of the Fancy, it was apparent that they were much more guarded around Cruikshank. I, on the other hand, was granted much more privileged access.

I was even graced with an audience by Ikey Solomon himself, the so-called ‘Prince of Thieves,’ then at the height of his power and at the head of a criminal empire that dwarfed even that of the legendary Jonathan Wild in the last century. I found him to be an intelligent and erudite man, and nothing like his later grotesque depictions in popular literature, wherein every Jew is a ridiculous devil. He was sharp featured, but no more so than Cruikshank, well turned out, and very well spoken. His only real concession to the fashions common to his race was an obvious love for rings, of which he sported several on each hand. He had sent for me with a different kind of trinket in mind, which, with a fence’s instinct, he felt sure would be of interest.[10]

We met in a candlelit tent in Stanfield Park, in which Solomon held court like a general on the eve of a battle, which was exactly what he was, only the battle was a championship bout between Jem Ward, the ‘Black Diamond,’ and Tom Cannon, the ‘Great Gun of Windsor.’ I was ushered in with great solemnity by a well-dressed bodyguard, no less terrifying for the cut of his coat, who took up a sentry’s position between me and the exit. Solomon was on an ornate chair and attended by a servant, who at a glance from his master silently provided me with a straight backed chair and a glass of very fine sherry.

Solomon addressed me imperiously, but not without grace. ‘So you are the last of the notorious Sikes gang,’ he said, regarding me with his deep, dark eyes.

‘I have that honour, sir,’ I replied, meeting his gaze with a bravado I did not feel.

‘You read for them, I believe,’ he said. He had me there. He knew I was no criminal. I nodded awkwardly but said nothing. ‘Don’t worry,’ my dear,’ he said with a smile, ‘your secret is safe with me.’ I returned his benevolent smirk and took a large pull on the sherry. ‘I have something,’ he continued, ‘that I think might appeal to you.’

He reached into the pocket of his elegant waistcoat and withdrew something on a chain that was not a watch. He held the object up before my eyes by its chain, the light of the candles reflecting dully off its sides. It was Nancy’s locket.

‘My God,’ said I, taken by surprise, ‘where did you come by that?’

He looked suddenly serious. ‘I come by many things, my dear, and where and by whom is of no concern of yours.’

I recovered my composure quickly. ‘Forgive me,’ I said, ‘I meant no disrespect.’

‘If I thought that you did, my dear,’ said he, with another disarming smile, ‘then Mr. Smith would have handed you your liver by now.’

‘That is true, sir,’ agreed the bodyguard, ‘although I would have taken no pleasure in doing so.’

I assured him that neither would I. The butler coughed discreetly, indicating that bearing silent witness to such horrors was included in his job description.

Solomon, meanwhile, had sprung the locket. ‘I had it in my mind that you might be the young man depicted herein,’ he said.

I shook my head sadly. ‘That was her son. I know not his name or his whereabouts.’

‘I see,’ said Solomon. He thought for a moment, turning the cheap bauble in his fingers.

‘May I ask you something?’ I said, carefully.

‘You may.’

‘Do you know why Bill did it?’

‘All I heard,’ said he, ‘was that it was a crime of passion. A foolish reason, for there is no profit in it.’

‘Must there always be profit?’ I asked him quietly.

‘You are an idealist, Mr. Vincent, but you are young,’ he said, ‘it will pass.’ I knew better than to push him further. ‘I fancied,’ he said, finally, ‘that this item might be worth something to you, beyond its usual exchange value.’ He lingered on the word ‘usual,’ for the locket was a worthless piece of tin.

‘It would mean a lot to me, sir,’ I admitted.

‘You loved her, of course.’

I nodded, mutely.

‘As did we all,’ said he.

‘She was my first love,’ I confessed.

‘And first love never dies,’ said Solomon sadly. He tossed me the locket and bade me farewell. ‘You can pay my man on the way out,’ he said.

I had no idea to what I had just agreed, but knew better than to argue. Fortunately, Smith only tapped me for five bob, which was cheap at the price. I fastened the locket about my neck and trudged off in search of Egan and a large gin. I wore the thing for years after, until I fell in love again, or so I thought at the time, and was only allowed to retain possession of it by claiming that the portraits were of myself and my late mother.

My mentor was impressed. ‘It took me years to see that one close up,’ he said.

Egan’s ticket had been his gift for language. Just as I had done in the Marshalsea, Egan had, by necessity, mastered the Flash tongue at the Fancy, the deliberately obscure and exclusive anti-language of the punters. Had he not become quickly bi-lingual around that lot, he might have been taken for a beak, a peeler or a maw-worm and never been heard of again. And if accused of using a little too much of the slang in his writing, he would reply that he purely employed ‘the strong language of real life’ because his intention was ‘to report, without embellishment, living manners as they arose.’ This he described as ‘New Journalism.’

It was my ability to likewise converse in St. Giles’s Greek, combined with my capacity to write to a deadline, which made me so appealing to Egan. The brothers Cruikshank were not writers, and the original Life in London had been envisioned by them as a series of engravings with Egan hired to provide a modest accompanying text. The billowing and highly successful serial that it had become was all down to Egan, an easy-going picaresque journey down the dark side of the street, all written entirely in the vulgar tongue. Reading Egan was an exhilarating experience, and I was immensely flattered when I realised that he saw in me himself as a young writer, or ‘fresh meat,’ as he put it, because he took nothing seriously save deadlines.

Needless to say, I was never able to approach his level of sheer Blarney, but I could still act as a suitable ghost to keep the story running on time, as well as covering a fair few fights under Egan’s own byline, ‘By one of the Fancy.’ (As these events were entirely illegal it was prudent not to report under one’s own name.) The money was good, and through a solicitor recommended by Egan I set about anonymously repaying my father’s debts, a process that would still take many years at my current level of income. Freddie I could have bought out immediately, but I needed him where he was. Having witnessed how he cared for my sister, I trusted this gentle soul more than I did my father to keep her healthy and safe. My father meant well, but like most men he was worse than useless around small children. I also arranged that every week a parcel of food should be anonymously sent to my family. I knew my father would not speak to me, so this was the best I could do for Sarah and Freddie. When I had dreamed of achieving moderately good fortune through the labours of my pen, this was not what I had envisioned. The gesture helped with the guilt though, but it did little to ease the grief.

As ‘The Author of “Wilhelmina” & co’ I was also allowed to return to my romantic roots in the paper, although it was Egan’s belief that the mixed reviews of the late Reverent Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer indicated that gothic fiction, although fun while it lasted, had largely shot its commercial bolt. I still wrote several new Tales of Terror for Egan, although it soon became clear that what he was really after was a gothic Life in London, sensational reportage given an additional macabre dimension by its association with my fictional credentials, but essentially factual and contemporary. Egan always knew what sold, and had covered the trial of Thurtell, Probert and Hunt. There the Prize Ring and the gothic had met as the ringleader, John Thurtell, was a trainer well known at the Fancy. It was a popular murder, and I still recall the verse written upon it by Will Webb:

His throat the cut from ear to ear

His brains they punched in;

His name was Mr. William Weare,

Wot lived in Lyon’s Inn.[11]

This was hardly a challenge, for beneath the fashionably façade that Egan and Cruikshank had constructed, the rookeries of the East End were already downright infernal. I think he wanted a murder a day, which was almost but not quite feasible, although I suspected (wrongly as it turned out), that the same story so often repeated would hardly fly off the newsstands. I have since learned that what audiences mostly want is something reassuringly familiar, in which their own view of the world and attendant opinions are essentially ladled back to them.

This work did not sit so well with me as reports from the Fancy and the Daffy Clubs, and smacked rather too much of the new broadsheets that had so appalled me in the Marshalsea. But I was in want of money and eager to please, so I fooled myself into believing this to be an opportunity, as has since often been my wont when it comes to a new penny-a-lining position. Egan said that I was merely moving from the theory to the practice, and I am ashamed to say that I had a gift for such grim business as well.

Looking back, the formula that we arrived at, as a result of observation and experiment, very much anticipated the later fodder of the Illustrated Police News and its imitators. Our staple was reporting on horrible murders, suicides, violent accidents, discovered corpses, apparitions, animal attacks, and, my least favourite category, executions, most of which were true, unless it was a particularly slow news day. Egan employed a variety of informers, from street folk to policemen, and a productive working day would usually commence when some chit or chick-a-biddy would turn up at the office in Great Marlborough Street to tell us that a body had been found at such and such a place and in such and such a state. After a while I learned who was more likely to be telling the truth, and to never pay in advance.

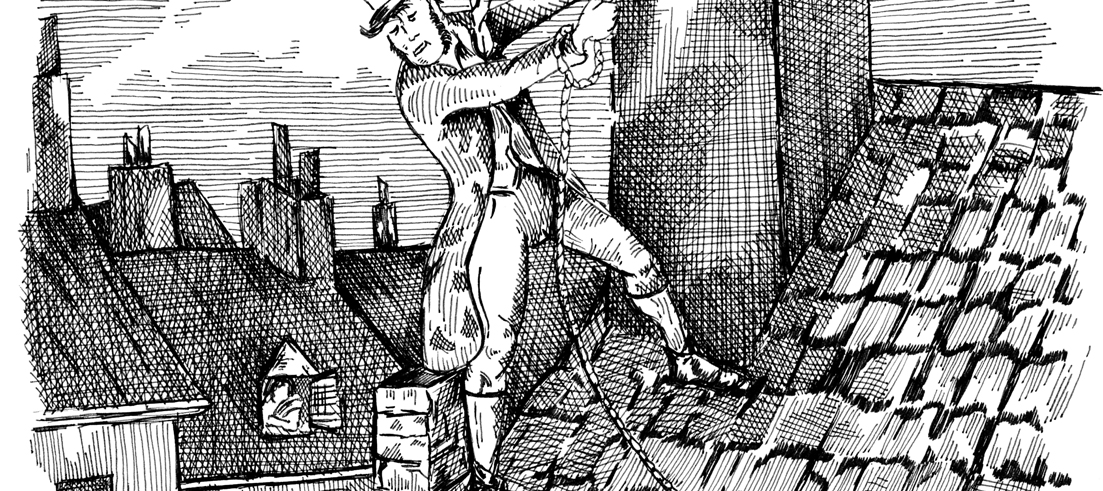

It was gruesome work. In the first six months I reported on dozens of accidents and atrocities, too numerous to cite in full. I particularly recall the strange case of a woman incarcerated and starved to death by her parents in a boarding house in Penge; a spate of garrottings in Lewisham; a somnambulist decapitated by a carriage wheel on Shooter’s Hill; a vagrant eaten by dogs on Chadwell Heath; grave robbing in Shoreditch; a deadly display of elephant teasing during a parade along the Strand; baby farming in Brixton; a self-crucifixion in Croydon (not uncommon, I discovered, although they could never manage the final nail); a fatal affray at a gaming table in Holborn; a clergyman killed by a cricket ball at a charity match in Hyde Park (left hand drive to mid off); a lethal encounter between a mail-sorter and a lunatic at the post office in Lombard Street; a badger on the rampage in Twickenham; a young wife in Deptford restrained and driven insane by her husband’s relentless tickling; an idiot boy thrown upon an open fire in Fulham; a little girl in Whitechapel blinded by her parents to make her a more effective beggar (again not an uncommon practice); and a nun raped and strangled on the steps of St. Anne’s in Limehouse.

You could not measure the human misery on those streets. Corpses sprouted like weeds. I saw as much rotten death as any diener or coroner, from bodies dumped on waste ground by their killers to those who simply died on the street of poverty or drink, gnawed upon by rats and, in one case, pigs, to skeletons walled up or buried in cellars and discovered by plasterers and builders in private and public buildings all over the city. The Thames, meanwhile, was as awash with carcasses as the Ganges. There were the stupid drowned, like the broken-hearted suicides that leapt from every bridge in London on an almost daily basis, and those too inebriated to watch their step. Then there were the victims; men robbed and killed to keep them quiet, women stabbed and beaten, sometimes for love, mostly for sport, and the children, so many children, unwanted and drowned like kittens. Very few of those responsible were ever brought to justice, and most of the hangings I had the misfortune to witness were for minor crimes against property.

I swear to you that not a single one of these stories was an invention. ‘Such intelligence,’ Egan was fond of saying, ‘is more than enough to keep a man at home with the curtains closed, and reading nought but The Holy Book.’

This was an uneasy jest, for I have noticed that few indeed, who have seen such things as I, will allow themselves the full insight into the true nature of the human experience that accompanies the vision: the certain knowledge that there can be no God, and that the only meaning to life is that it ends, farcically, violently, and without dignity, point or purpose.

To find my way back from the dark places was a problem; not physically, but spiritually, although I confess I often found myself lost in the rookeries of London, surviving only because I could lapse into the Flash and generally talk my way out of trouble. At these times the drink was not my friend. I never knew which way it might take me, whether into comedy or tragedy, and a bingo-fuelled depression could cost me dear, rendering me incapable of writing a word for days. I therefore started to occasionally purchase laudanum, which could be had for a penny a bottle at any street apothecary’s, in order that I might sleep after reporting upon a particularly unpleasant demise.

The ghost stories were much less frightening. These were reported like any other news story, and I wanted so much to believe in them. I was still a very young man, and Solomon was right, I was an idealist. Having rejected religion, I immediately replaced it with a different delusion. I still yearned for magic, and longed to witness proof of some sort of afterlife. It was at best a childish stance, and at worse hypocritical. Rest assured that I knew it was so, and that I was falling into the trap of many an author of the literary fantastic by coming perilously close to believing in his own bollocks. The sightings and accounts related to me by the most earnest of witnesses, who I am sure believed every word they said, were often very eerie and enchanting, but I never personally saw anything that led me to conclude beyond any doubt that there was enough evidence to support a supernatural interpretation. Who has not seen an old dark house, closed up and fallen into decay, from which after midnight weird sounds have been heard to issue: aerial rappings, the rattling of chains and the moaning of perturbed spirits; a house where apparitions are seen at windows, and which locals believe is unsafe to pass after dark, and which no tenant would occupy, even if he were paid to do so? There are hundreds of such houses in London, and every one has its own particular legend, tales of hauntings that seem more thrillingly plausible with every advancing second towards dusk, once you have taken up your position like a hunter in his hide. But when a man avers that he has seen a ghost he is passing far beyond the limits of the visible and into the realm of inference. He in fact sees something which he supposes to be a ghost. I witnessed this optical alchemy many times, in which the simplest trick of the moonlight became dreadful figures in the shadows. It is my belief that the events recently reported in New York will turn out to be much the same; those people will fall for anything.

My own phantasms were not so easily explained away, although I knew that they were no more real than the ones I reported upon. They would nonetheless come to me, out of the dark, the noiseless ones, the dead and the not dead, to gather about my bed: my mother, naked and obscenely wet, my sister reaching out grotesquely from the ragged cavern of her belly; my father, pointing, accusing, a silent scream unhinging his jaw; Freddie at his feet, starving, too weak to rise, his hand in his breeches, his sunken eyes imploring; and Flashy Nanse, dearest Nancy, her head stove-in and distorted like a melted candle. Her damp skirts up, she would straddle me, and I would taste her blood until I awoke in shameful security and slept no more. And they whispered to my heart to join them, and asked why I was still here. Were they not my family, they said, should I not be reunited with them all?

And, God help me, they were tempting. I felt their lack dreadfully, and thus far no amount of drink or doxies had relieved the constant longing so leaden in my soul. I knew that one must beware the view back, but still I would fret away the hours before the dawn, smoking heavily and internally debating whether or not to oblige these nightly visitations, to become one of my own stories: self-murdered, like Chatterton or Polidori, just another putrefying corpse with delusions of romance in a cheap garret with the rats at it. ‘Horrible discovery of a writer found poisoned in his rooms,’ would be the headline, accompanied by a suitably lurid illustration by Cruikshank.

But every night, just as it had been in the Marshalsea, I had not the courage. I would die soon enough, I would convince myself, at the conclusion of each nocturnal battle, probably from insomnia. My visits to the apothecary therefore became, by necessity, more frequent, just for a tincture that might help me pass a night in peace.

On one such occasion, quite late in the evening, a small, dark man with an unhealthy sheen about his features, who I assumed was waiting to be served after me, tapped me gently on the shoulder when I had made my purchase.

‘Perhaps you could spare a drop, sir,’ said he, for I’ve a terrible toothache and find myself temporarily financially embarrassed.’ He tried to press a filthy card into my hand. ‘You’ll take a note, won’t you, sir,’ he pleaded. He was visibly shaking, and his pupils were so dilated it appeared that his eyes were quite black.

He had played his hand too soon. ‘Away with you,’ said the druggist, placing a long cosh upon the counter for added emphasis. ‘Stop bothering my paying customers and go and grin in a glass case, for you’ll get nothing else from me.’

The little man slunk away, and I made sure that I took my leave in the opposite direction. He doubled back and followed me all the same, quickening his pace when the street became deserted and once more tapping me upon the shoulder, this time with considerable force.

‘I am the antichrist,’ he declared, ‘will you deny me?’

I raised my arm to strike him, but instead of drawing back he began to laugh. It was forced at first, but his howls of mirth quickly became utterly deranged. I bolted, but could still hear him when I turned the corner into Camden High Street, where I then lodged, shrieking behind me like a soul in torment.

That night I doubled my usual soporific dose to forty drops in absinthe and slept surprisingly well. I soon forgot about the strange little man, and took a most agreeable breakfast with Egan and Cruikshank the next morning. My working day began at about ten, with a tip from a reliable source that the mutilated body of a butcher’s wife had been discovered in Barnet.

Click here to read Chapter XIV

No Comments