‘I can fancy a future Author taking for his story the glorious action off Cape Danger, when, striking only to the Powers above, the Birkenhead went down; and when, with heroic courage and endurance, the men kept to their duty on deck.’

– William Makepeace Thackeray, speech to the anniversary

meeting of the Royal Literary Fund Society, reported in

The Morning Herald, May 13, 1852.

‘How do you like Forster’s Life of Dickens? I see he only tells half the story.’

– William Harrison Ainsworth, letter to Jack Vincent, January 25, 1872.

BOOK ONE

THE SHIVERING OF THE TIMBERS

We were approaching the islands of Madeira, about midway in our journey, the day we lost a man and a horse. The animal belonged to Sheldon-Bond, and he was considerably more put out by its passing than he was that of the human being that accompanied it into the void. The young subaltern remained in a foul humour for the rest of that miserable and ill-omened day, his unfortunate man, Private Dodd, getting the worst of it. I tried to avoid him, as there was already bad blood between us, but this was difficult given the confines of the ship. As he stormed around the deck like a vengeful wraith in a graveyard, I could read the message in his eyes when they connected with my own quite clearly.

My suppositions were verified when our paths finally collided in the corridor that led to the wardroom later that evening. ‘Do not dare to write about today’s events, you Chartist swine,’ he had said, his voice soft yet pregnant with menace, ‘or things might go very badly with you before we reach our destination.’

But I did, of course, damn him, for that was my job.

The accident happened towards the end of the forenoon watch. It was a calm, clear morning, and not unpleasant to be above deck. The air was far too still for the ship to go under sail; and, as was not uncommon, we were therefore becalmed while Whyham and his engineers made repairs to the engines. These were, like several of the ship’s company if truth be told, prone to seizures, as well as other mechanical ailments too various and incomprehensible to innumerate. Whyham, the Chief Engineer, was a good sort, and fancied he had found in me a mouthpiece by which he could share his passion for marine engines with the empire. He had therefore explained the working of this great machine to me at length, although I must privately confess that I had not the wit or wisdom to truly appreciate the functional beauty of the thirty foot connecting rod which was currently being straightened on deck by the ship’s blacksmith, an ancient and spark-scored creature who would obviously have preferred to work unhindered by Whyham’s constant and nervous interruptions. Although such delays drove our Captain to despair and distraction, they were a welcome break for the rest of us, when the weather was fine at least, affording a tranquil respite from the constant drone of those Tartarean engines.

It was at these times that Herbert Briscoe, a stoker from Liverpool, took it upon himself to provide us with some light entertainment. When the drift anchor was deployed and the ship relatively static, several blinking soot-stained stokers would emerge on deck to take the air; and if Speer, rather than Davis, had the deck, Briscoe was given leave to do his popular mélange act. He would begin by taking a running dive off the bow, after first hesitating to indicate mock apprehension like a Harlequin in a low opera, before expertly plunging into the depthless dark. He would then swim the length of the hull underwater, before surfacing astern to a muddle of Flash obscenities and enthusiastic applause, much of either stripe on account of the wagers placed upon the length of time it had taken him to run the keel, the winners dropping ropes that he might re-embark, temporarily cleansed of engine room filth and several shillings the richer. We would all count together in order that the timing be accurate, bellowing the numbers aloud as one. He usually did it in about two minutes.

I declined an offer from Private Moran to place a bet. A man of my means should never gamble. His countenance, in reply, was a strange combination of obsequiousness and contempt, suggesting that he imagined me a swell or a cheese screamer: either too full of myself to game with common soldiers, or opposed on ecumenical grounds. The reality was that with all his wheeling and dealing he was likely much wealthier than I, and that God was as dead to me as to him. I liked Moran though, and through his patronage I had been able to interview many of his companions. I therefore did something that would have appalled my dear wife, and responded by turning out my trouser pockets with an exaggerated shrug and a winsome smile. I doubt he believed me, but the old pirate rewarded me with a sympathetic grin before darting off into the mass of men crowding the rails in search of Briscoe.

I rejoined the count at sixty-five. Briscoe should now have been about halfway, just past the huge steam driven paddle-wheels on either side of the hull that would, were they in motion, have ground him to pie filling in an instant, like the victims of the demon barber of Fleet Street himself. I swear the old bake head was more fish than man. I knew many seamen did not swim, but Briscoe was not of that kidney. He loved the water as much as I feared it, for I could barely swim a stroke. I knew that this was a skill I should acquire in order to swim with my son, but I had thus far declined Briscoe’s offer of ‘a few pointers.’ He expected me to practice in the open water and I could not bear the thought of entering such a vast expanse of nothingness. To my mind, Milton would have done better to imagine the hellish void through which Satan travelled as the black Atlantic rather than some frozen wasteland. At least on land a man might have a chance, but consider the horror of being lost at sea, with no land in sight or beneath your feet, no cognisance of what moved beneath save your worst imaginings, and the odds of rescue so long that even Moran’s most reckless customer would shake his head and keep his money in his pocket. This was why many seamen to whom I had spoken would not learn to swim, a stance that might have surprised many but not me. No, I would not swim, especially in that God cursed ocean.

The count had now passed eighty, which was close to Briscoe’s best time on the voyage thus far (which was ninety-six seconds). While the count continued, I was distantly aware that Cornet Bond and his man were attending to the young officer’s horse, which like the other animals on board was corralled in a temporary but well-constructed stable on the upper deck. When the ship was not violently in motion, Bond liked to walk his horse so that it remained in good fettle throughout the arduous journey. He was a Lancer, and those men valued their mount above all else in the world; but as one of only two cavalrymen on board, Bond’s fellow officers obviously viewed his relationship with his horse as somewhat obsessive. I could sympathise, though I did not care for the man. I knew his type, and he, it would seem, knew mine. Nonetheless, he possessed a very fine horse, a young solid white gelding, and his attention to its care was admirable. If only he afforded his human subordinates the same level of kindness I would have been glad to have counted him an ally, despite his social rank. I could not hear him from my position, but I could tell he was berating his orderly, the long suffering Dodd, a gentle soul of twice the years of his master. I could see the petulance in Bond’s features (when he lost his temper he revealed his true face, which was that of a spiteful youth several years shy of twenty), while, similarly, he was always shouting at poor old Private Dodd.

The count approached two minutes. No one else was watching Bond, but I could see through the open stable gate that his horse was becoming agitated, like a child, by his mood. Dodd was hanging on to the frightened animal’s bridle as if his life depended upon his very grip, which looking at his officer it may well have done, while Bond, to give him his due, attempted to calm the creature by whispering in its ear. Between them they guided the nervous animal onto the deck, Bond now taking the bridle, to Dodd’s obvious relief. The upper deck was perhaps thirty yards in length, and was cluttered with lashed down military equipment and a complex web of rigging. Mindful of obstacles, Bond carefully walked his horse through that decidedly unsuitable paddock.

Would that we could communicate with the lower forms, for how could such a creature possibly have comprehended the point and purpose of sea travel? I was reminded of the feelings of helplessness attendant in the care of the very young, when one cannot explain to a baby yet to acquire language why she or he must be cold or sick or hungry. Perhaps, I thought, Bond communed with his horse as I did my son, by means of a kind of desperate kindness, a non-verbal reassurance made of soft sounds and gentle gestures.

Would that we could communicate with the lower forms, for how could such a creature possibly have comprehended the point and purpose of sea travel? I was reminded of the feelings of helplessness attendant in the care of the very young, when one cannot explain to a baby yet to acquire language why she or he must be cold or sick or hungry. Perhaps, I thought, Bond communed with his horse as I did my son, by means of a kind of desperate kindness, a non-verbal reassurance made of soft sounds and gentle gestures.

When I saw my boy again he would probably be talking in quite complex sentences. How I hated to miss such a significant development. I also feared that this thinking, speaking child would not remember his father, despite our early attachment. I banished the thought as best I could. In that environment, I could ill-afford the kind of black mood that such ideas engendered. His mother would not let him forget me, I decided, and when the Morning Chronicle paid me I would be better placed to raise a family. My present situation was, as my friend Reynolds put it, ‘a tour of duty,’ much like that of the soldiers and seamen about whom I was charged to write. It was a necessary means to an end, and at least I was still working, albeit in the face of my original promise to Grace that I would never allow my career to remove me from my family. No, that was another train I must let pass me by. We needed the money, and there was no decent work for me in London anymore.

The count was by then becoming decidedly less enthusiastic. How long may a man hold his breath under water, I wondered; two, perhaps three minutes? If our collective enumeration was accurate, then Briscoe was now approaching three minutes without air. Speer, the Second Master, was looking decidedly queasy. The mood of the men on deck had changed as well, and they looked to the officer in charge for guidance, for a clear sign from above. No one counted after the fourth minute has passed. We stood in helpless silence while Speer weighed up his options. Even Bond had come to a halt.

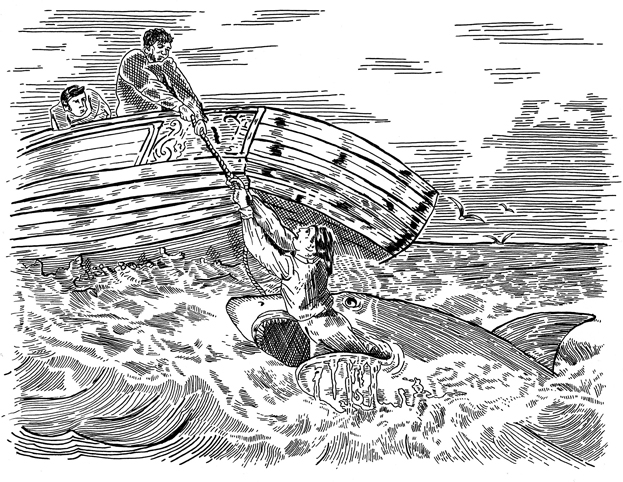

‘Man overboard!’ screamed Speer. The spell was broken, and the seamen exploded into activity. Aldridge sounded the alarm from the poop, hammering on the great bell as if the French were attacking. Speer bellowed the order to lower a boat, putting Able Seaman Blake in charge of the rescue. There was a deafening babel of competing voices. Everywhere seamen were shouting, mostly trying to clear the rest of us from their way.

It was clear that Bond and his horse were a serious obstruction. ‘Mr. Bond,’ yelled Speer above the general cacophony, ‘will you please remove that animal.’

It was my guess that Bond was so taken aback at being thus addressed that he slightly relaxed his grip on the bridle. In that instant, the horse, already panicked by the general alarm, bolted. Seamen scattered like churchgoers menaced by a vagrant, and, as if to confirm his master’s frequent boasts that he could have been a steeplechase champion, the horse cleared the port rail like a five bar gate. Bond screamed like a woman and ran to the bar, followed by several of the men, myself included. The hapless animal had survived the drop and was swimming, quite adeptly, in an uneven circle about five yards from the ship. Blake had steered his boat in the direction of the commotion, hoping no doubt that someone had spotted Briscoe. Bond was shouting at Blake in the gig, but the latter was signalling with his hands that there was nothing he could do. Bond ran off to request the deployment of the windlass.

‘This is better than the penny theatre,’ said Private Moran.

All the senior officers were now on deck; Major Seton looking nervous, Brodie, the Acting Master, looking annoyed, and Salmond, our Captain, looking drunk. Drake, the marine Colour Sergeant, was ushering the women and children below deck, while Lakeman, the mercenary, struck a long match and lit a cigar. There was still no sign of Herbert Briscoe.

It looked as if Bond had managed to convince Speer to save the horse, and the ship’s huge cargo winch was now swinging seaward with the aid of half-a-dozen ordinary seamen. The plan, it appeared, was that Blake would send a couple of men into the water to get the harness under the horse, but before the winch could be lowered to retrieve the terrified animal, a shout went up from the masthead.

‘What the devil`s that?’ said a man next to me, shading his eyes with the flat of his hand, ‘a whale perhaps?’ We all strained to follow his gaze. A dark shape in the azure waters lay.

An animal fear came over me, and I suddenly wanted to back away from the rail. That was no whale. We had seen such creatures on the voyage, and despite their immense size they had none of the menace that this shadow conveyed. Everywhere men began to bellow, ‘Shark!’ at Blake and his crew, who in their turn looked around in obvious panic.

The great fish approached Bond’s helpless mount and the horse began to swim frantically back towards the ship. The shark pursued unhurriedly, surfacing as it passed its prey, dwarfing it in size as it did the small open boat. It must have been fifteen feet long at least, if not more.

‘Christ and all his holy angels,’ said Moran.

I had read of sharks, and also written of them, but even the most lurid accounts of the illustrated press or my own imagination had not prepared me for this terrible apparition. There was something ancient in the simplicity of the beast. It was a flat, implacable grey with no features save dead, black eyes, like a doll or a devil. Bond watched the enormous animal glide through the clear water in total horror. I saw him call to a nearby marine, who unslung his rifle and handed it to the young officer. Bond raised it at once, sighted carefully and shot his beloved horse a fraction above its left eye. He hung his head, and offered the musket back to the shocked leatherneck. We became aware of more shots then, as the other marines fired on the shark, which was still close to the surface and circling the twitching carcass of the horse. Comparing the animal with the now limp body of the horse, I inwardly increased my original assessment of its length. I saw four shells strike it around its huge dorsal fin. Blood flowed from the broad grey back, but the shark did not even slow its pace or bother to dive. Then its huge triangular head seemed to hinge back, and its terrible mouth fastened onto the horse`s flank, shaking from side to side as it tore away a great chunk of marble flesh. Fascinated and appalled, I watched as the water turned to blood.

Lakeman, who had thus far taken no part in proceedings, called for his man. The steadfast Private McIntyre was immediately at his side. Words were exchanged, and McIntyre scurried off as Lakeman strode purposely towards us, still casually smoking. The men parted as he approached the rail, leaving the two of us together. Lakeman nodded in greeting but said nothing, watching the monster feeding below. McIntyre returned carrying a long rifle.

‘Loaded?’ said Lakeman.

‘Of course, sir,’ said his batman.

Lakeman held the rifle in the crook of his arm and inserted cork earplugs. ‘You might want to cover your ears,’ he told me, a trifle loudly, raising the rifle.

There was a crack of thunder and a split second later the shark’s great head exploded in a shower of blood and bone. Shuddering, it fell away from our horrified eyes, disappearing beneath the flat red surface of the water like a sinking ship.

‘Will sir take nuts or a cigar!’ cried Lakeman, delighted with his shot. A cheer went up from the deck, and Blake and his crew visibly relaxed.

‘Brute,’ whispered Bond, who had joined us at the rail. ‘Rotten filthy brute.’

The air around us was muddy with foul tasting smoke. Lakeman tossed the gun back to McIntyre and threw me a wink through the murk. He removed the earplugs and dropped them into McIntyre’s waiting palm. My ears were ringing like a man in a bell. ‘Elephant gun,’ he announced, ‘2 bore: half-pound ball. Hard on the arm and a devil to load in a hurry, but it’ll pretty much stop anything.’[1]

‘You might want to start reloading now then,’ I said, as, God help us, there were more of them, three, at least, tearing into the body of the horse.

Lakeman, however, had lost interest. I received the impression that he had been conducting an experiment and, satisfied with the result, he saw no reason to repeat it. ‘It’d just be shooting fish in a barrel,’ said he, strolling away with the nonchalance of a winner at a faro table, McIntyre trotting dutifully behind.

Bond and I were left alone. I awkwardly tried to express my sympathy.

‘What would you know about it?’ he said vituperatively.

I shrugged and kept my own counsel as he took his leave. Needless to say he was right. I really didn’t care how he felt about anything, and as the probable fate of poor old Herbert Briscoe, forgotten in all the excitement, occurred to me, I ceased to concern myself with Bond or his bloody horse.

There was nothing for it but to finish the repairs, and when we were once more under weigh the sharks followed. Over dinner there was talk of some sort of memorial service for Briscoe, but during the discussion I found myself suddenly distracted and preoccupied by a curious childhood memory. The more I tried not to think of it, the more vividly I recalled an incident with a cat I had once owned. One spring, a baby sparrow fell from its nest in an elm in my parents’ garden, and my little cat was on it before I could help the unfortunate bird. She sat under the same tree every day for the rest of the month, waiting for another fledgling to fall.

Click here to read Chapter II

No Comments