A few passengers, including myself, had embarked at Portsmouth a month earlier, on the first day of January, 1852. This gave us a day or so of relative peace in which to become acclimated to the ship and to each other, before she took on the bulk of her human cargo at Cork. The 12th Foot (the East Suffolks) were already on board, seventy-odd men and their officers, Granger and Fairtlough, as well as the mercenary Lakeman and his contingent, the Lancers Rolt and Sheldon-Bond, and about a hundred Highlanders from the 73rd, 74th, and 91st Regiments, including Major (soon to be Lieutenant-Colonel) Seton and Captain Wright, the senior military officers on the ship.

With the beginning of the New Year our journey also commenced, with a brief, uneventful jaunt around the south west coast and into the Western Approaches. As I had anticipated this adventure with a cold, sick dread for several weeks by that point, I was relieved that modern sea travel notionally appeared much less arduous than my research and limited personal experience had led me to surmise. On the contrary, I supposed that my initial concerns were groundless, and that sea legs were much more easily acquired than I had previously thought. Looking back, I was as a man receiving the first stroke of a surgeon’s blade or a sergeant’s lash, naively believing that such a short sharp shock could be endured, and not at all considering the duration of the torture. I recall my wife making a similar error of judgement regarding the pain of labour, assuming the initial stage to represent the whole, and wondering aloud to the attending midwife, with her usual sunny wit, why there was so much fuss and screaming normally associated with the miracle of birth. This misplaced bravado occurred a while before the true contractions commenced, turning her inside out with agony for the next five hours or so. And this was a remarkably short labour, I am told.

Despite her reassuringly gentle passage through the smooth waters of the Solent, the ship possessed an eldritch aspect, at least to me, from the beginning. There was something ancient and foreboding about her, the paradox being that she was a relatively new vessel, built only a dozen years or so before. As a steam powered ship of iron, she could not, in fact, have been more modern. I should note here that I tended towards Luddism as a general rule in those days, although if pushed I would concede that some of the new technology was not without a certain merit. I was grateful, for example, for rail travel over those interminable coach journeys, while pulp mills and steam driven paper making machines were a definite boon to my profession, bringing printed knowledge to the common man for the first time in history. Nonetheless, I feared that the savage pace of change, as Mr. Marx and Mr. Engels had so persuasively written, was of little benefit to my class.

My nostalgia for less complicated times did not, however, extend to matters maritime, and I found the political and popular arguments in favour of conventional wooden warships over iron and steam to be ill-informed, backward looking and ridiculous. I expressed these views to Captain Salmond upon our first meeting, and was invited to dine at his table thereafter. This was a fortuitous turn of events for me, given that the salty old cove liked a drink and bled freely, while my personal supplies were far from endless. (The fact that my sea chest audibly clinked was a source of much ill-disguised amusement to the bluejackets who had conveyed it to my quarters.) He also had coffee, which was a rare treat.

To be a journalist, one must be able to get the measure of a man very quickly and, in doing so, gain his trust whether he be of high or low estate. This was a facility I had always possessed, which I took to come from my youth, when I had to learn quickly how to adapt to very different social environments. Robert Salmond R.N., Master and Commander, was reasonably easy to read. He was a disappointed man. I had the hairy old spud hooked and landed as soon as I asked him where his guns should have been placed. In an impossibly low voice that seemed to rise from the very depths above which we precariously sat, he solemnly described the two 96-pounders mounted on pivots fore and aft, and the four 68-pounders, paired each broadside, imaginary guns that had been originally intended by her designer, commissioned, as he was, to build a warship not, said Captain Salmond, ‘a damn troopship.’

The ship and her architect were the victims of political expediency. John Laird was a visionary, who staked his reputation and his business on iron over oak. Cockburn, the First Sea Lord, was of a similar opinion, convincing Peel, then in his second term, that the future of England’s undisputed mastery of the waves was cast in iron. The frigate Vulcan was therefore commissioned by the Admiralty to be built by Laird as part of a proposed new fleet of iron vessels. Such armadas do not come cheap however, and not everyone in government approved of such unproven, they said, extravagance. Wooden ships had been good enough to best the Spanish and the French, argued the traditionalists. Would Nelson have triumphed at Trafalgar were he in command of a fleet of kettles, they demanded, did Raleigh assault Cadiz in a bathtub? It was a collision between the old world and the new, and for once the industrialists were routed. I covered parts of the story myself, although while most papers, whether for or against, were keen to support the Royal Navy in its on-going maintenance of world peace, we at the Northern Star continued to argue that the planet was, in reality, in a constant state of turmoil, much of it engendered by us.

The change from wood to iron thus proved much more contentious than the relatively smooth progression from sail to steam. Lobbyists for the timber shipbuilding industry argued that ships built of iron could not possibly float, despite the re-invention and refinement of the watertight bulkhead by maritime architects such as Laird. It was also widely believed that iron hulls were more easily subject to catastrophic damage than wooden ships, and there were also issues raised regarding the effect of the iron on magnetic compasses, a constant deviation, easily corrected, but presented in the popular press as damning evidence for the prosecution. As I reported at the time, many of these critics also had their own interests and investments to protect. I thus collected a few new enemies along the way, but it was not the first time and, in any event, that is always the nature of my profession.

By the time Laird had won his contract, Peel’s administration was on its last legs, battered by recession and deficit, and rotted from within. In my opinion, he gave ground on the naval budget in order to hold out long enough to repeal the Corn Laws. Cockburn’s building programme was cancelled, and Peel went out the following year. When Laird finally launched what was to have been the frigate Vulcan, completed only because she had been too advanced to scrap, she hit the water a hastily redesigned troopship. Just as Juno had cast her infant son off Mount Olympus, the Admiralty had rejected their Vulcan, pulled her teeth and prosaically re-named her Birkenhead after the city of her birth. The presence of the god of fire and iron was now marked only by an incongruous effigy of him as the ship’s figurehead, either left in defiance by Laird or not considered worth the bother of changing.

‘I have often felt that Mr. Laird and myself have much in common,’ Salmond confessed, ‘although we’ve never actually met.’

‘I have often felt that Mr. Laird and myself have much in common,’ Salmond confessed, ‘although we’ve never actually met.’

‘In what way?’ I said, wondering but not asking if Laird also had a beard like a wild hedgerow in winter.

‘In the manner of life seeming to promise one thing, and then delivering quite another,’ he said.

In that sense the Captain and I were also of a similar stripe. This affinity was more than I felt able to volunteer at that juncture, although no doubt he privately knew full well that Mr. Dickens and Mr. Ainsworth had no need to leave their families and supplement their incomes by freelancing as special correspondents, despite my mask of professional respectability. So natural was my performance by then that I sometimes almost fell for it myself.

Salmond loved his ship though, but it was obvious to me that he could never quite master that nagging feeling that he was no more than the driver of a sea-going omnibus, having previously seen active service on the Retribution and the Vengeance. Nowadays he carried passengers, always anathema to a sea captain of the old school, men and their families away to wars in which he would take no part. A man can justify his place in the world in many ways, and Salmond knew that ships such as his own were as much an organ of empire as the fast frigates, but, said he, again in confidence, ‘There are captains of warships, and then there are captains of troopships.’

He could trace his seafaring lineage all the way back to the reign of Elizabeth, with all that means to any navy man. He knew that he could have been more than he was, and you could see in his salt blasted eyes that this intelligence gnawed at his very soul. It was equally obvious that this frustration at his own sense of failure was not easily kept at bay by any intoxicant he knew of, and as a well-travelled man he knew of quite a few.

Having no military laurels to gain, Salmond had determined to distinguish his command by virtue of speed and efficiency. He therefore promised me that we would make the Cape in forty-five days, as against the naval and mercantile average, which was sixty-four. This was music to my ears, for every day spent away from my family was torture. If Salmond was as good as his word, I would spend about three months at sea, there and back again, while another three at the most should garner more than enough material from the regiments garrisoned around Port Elizabeth and in country for a decent series of articles. With a bit of luck I would be home before my son’s third birthday.

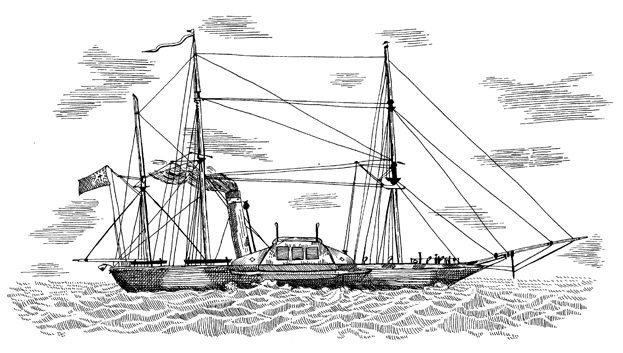

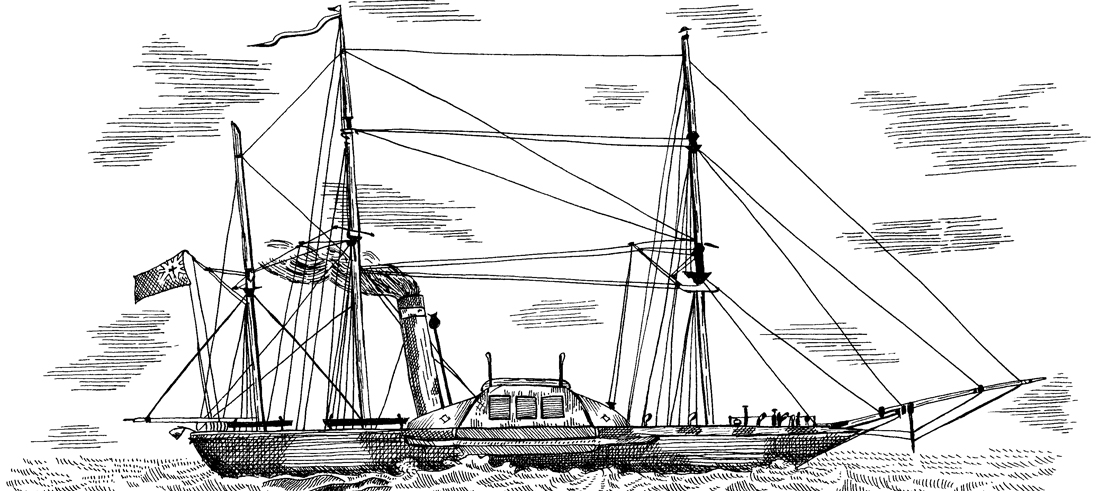

I did not share these thoughts with the good Captain, but when I first spied his ship, she seemed an awkward marriage of sail and steam and wood and iron. She was rigged as a brigantine, but carried a tall funnel between fore- and main-masts, combined with a pair of paddle-wheels set on the outside of the hull, each a good half-dozen yards in diameter. Her hull was constructed of riveted iron plating, while her decks, paddle-boxes and masts were made of wood, the contrast made sharper by the paintwork, which was black on the iron and white on the woodwork. The ship was small by the standards of modern liners like the Oceanic, but back then she dwarfed all other vessels in the harbor, being a good seventy yards from stem to stern, and displacing a couple of thousand tons. The surrounding cutters, gigs and fishing boats were toys in her presence, fit for nothing but the bathtub or the boating lake.

Silent, lonely and sublime she was. Against the fading light of a brittle winter day the men in the triple-masted rigging reminded me of spiders, while the miserable looking figurehead glared balefully down with a look in his eye that I generally associate with management and magistrates rather than celestial metalwork. Child Rowland to the dark tower came, I had thought as I mounted the gangplank.

To my considerable relief I was accorded a private berth. The icy grey walls recalled the box of a stone jug, yet for all the unpleasant associations that this brought forth, I remained grateful to have a place to myself in which to retire and write. The men in the troop decks had naught but eighteen inches of hammock space to claim as their own, buried in low bulkhead compartments so airless that lamps and candles barely burned. When I paid a visit to the lower decks I felt like a miner, bent over and making my way to the coal face through ghostly lamplight; half crawling through low, jagged openings that snagged and scratched, cut as an afterthought into the ship’s bulkheads to improve the movement of the troops.

It was all too easy to lose one’s way, and to my shame I did just that the first time I descended into the blackness with the intention of documenting the layout of the ship for my readers. I collected a similarly bemused ranker along the way who had been sent on an errand from the troop deck and was now lost in the labyrinth. The man was a private in the 12th Foot name of Edward Moran, who, like me, had come aboard at Portsmouth. It was well worth my while to engage him in conversation. I needed a conduit to the soldiers in order to do my job, and I was much more likely to gain their trust if presented by one of their own rather than an officer. Upon making his acquaintance, I was gratified to learn that the private had read my work, and was particularly fond of The Darkman’s Budge (my life of Joseph Blake, or ‘Blueskin’), and The Black Grunger of Hounslow, which had both been serialized by Edward Lloyd.

He was a typical London Irishman, possessed of hair even darker than my own, and keen, intelligent eyes. ‘Love and murder suit me best, sir,’ said he, ‘but your stories set me a thinking too.’ I took from this that he had radical leanings, but politics aside I was absurdly flattered, especially when he went on to describe my fair weather friend Dickens as a jawbreaker and an anthem cackler of which he could make neither end nor side. ‘I’d like Mr. Dickens fine,’ he said, ‘if only he’d kept to being funny like he was in the Pickwick Club.’ I was compelled to agree, and had given up after Dombey and Son, a turning point in English letters so I’ve been told, but damned hard reading.

My new found friend had never seen the inside of an iron ship either, and had no more idea of where to go than I. An orange glow in the distance suggested lamplight, so we decided to head for that, in the manner of moths to a flame. But when the sepulchral light expanded, instead of arriving at the troops’ quarters we suddenly found ourselves at a dead end, face to face with two unblinking marines, armed and at attention, at either side of a great iron door. Oil lamps hung overhead, casting long shadows that gave the guards a similar aspect to that of the ship’s figurehead, as if they too were cast in heavy metal.

‘Halt! Who goes there?’ demanded one of the frozen leathernecks, his musket suddenly rampant in the most alarming manner.

‘Friends,’ said my companion, gently diverting the long barrel of the gun with his index finger. Behind him, I shuffled around like a schoolboy, too nervous to appreciate that at least I could stand up straight for a moment. The marine growled at us. ‘I take it this ain’t the soldiers’ billet?’ ventured Moran.

‘This is the magazine, private,’ replied the marine, with danger in his eye, ‘there’s nothing for you here.’ He ignored me completely. This was insulting, but also a profound relief. I made a mental note that the magazine was physically guarded, instead of simply locked, which seemed unusual.

His comrade had been of a more understanding disposition. ‘Ain’t you got a guide then, mate?’ he asked gently, although he moved not a muscle below the neck as he spoke.

‘No, your worship, we have not,’ said Moran, ‘it’s more of a case of the blind leading the blind.’

‘So I see,’ said the second marine, dismissing me with a glance no doubt reserved for civilian males, which had no relevance in his world whatsoever.

‘I am The Press,’ said I, feeling the need for validation.

‘Then God help us,’ he said, with not a trace of humour. ‘There’s supposed to be bluejackets showing you lot where to go,’ he continued, in the overly measured tone of one permanently exasperated. ‘Take yourselves back where you came from until you see a set of steps. You came down one deck too many.’ He nodded towards the dark passageway behind us. ‘Now shake your trotters and don’t come back, and we’ll say no more about it.’

‘That’s very kind of you,’ said Moran, with a lick of the Blarney about him. The first marine then dismissed us with a dreadful oath, and we beat a hasty yet, I hope, dignified retreat; a manoeuvre to which I, in common with the British Army, was not unaccustomed.

A distant thunder, initially suggesting the movement and speech of a large body of men below decks had next led us along another narrow, dimly-lit passageway. As the sound became more unearthly and cacophonous, this new section of freezing maze coughed us out into the nave of a vast cathedral raised in praise of the new science. It was not soldiers we had heard but engines, unfeasibly large engines, their howl weirdly distorted by the acoustics below deck, and all being primed for our imminent departure.

My companion swore for several seconds, never, I noted, once repeating his self. He was in need of a berth not, as he put it, a frimicking manufactory. A dozen trains seemed crammed into the belly of the ship. Shimmering waves of heat from massive boilers and condensers seared our faces, while gigantic cranks spun storms of deafening volume to burst the eardrums and rattle the bones. Engineers swarmed around the machinery. Some dripped oil on exposed levers and cogs; some listened, with the benefit of ear trumpets, to shafts spinning in highly polished bushes, and yet more checked chronometric dials and screamed the readings to each other. Half naked beings, corded muscles blacked by soot, fed the insatiable furnaces. We stood there like tourists who do not speak the language, gazing uselessly into a cavern as tall as the ship herself, until a stocky man with a miner’s face looked up from the huge dial it was seemingly his sole task to carefully monitor, and waved us out with his slate, as if swatting flies.

Once more we entered the gloomy passages, miserably retracing our steps. The ship seemed to have no end. ‘We are as Jonah, my friend,’ I observed, ‘trapped within the belly of a whale.’

‘Mark that place we’ve just been well, sir,’ he had shouted back, ‘for that’s where we’ll go when we die.’

More by luck than judgement, we found the troop section on the third attempt, forward of the engine room. By this point I would not have been surprised to have emerged under water. Those that knew Moran hooted from their hammocks.

‘Get lost did you?’ said an immaculately turned out marine who was obviously in charge, and whose features were distinguished by an ugly, livid scar beneath his chin. Like his fellow leathernecks at the magazine, he did not spare me the time of day.

‘Tour of the ship, Colour Sergeant,’ said Moran cheerily.

These early arrivals had already chosen their spots and stowed their kit, keeping to a vague regimental order with the Cockneys at one end of the troop deck and the Scots at the other, separated, I later discovered, by a tight huddle of labouring lads from East Anglia and the Home Counties. I followed Moran around the long mess tables running the length of the vast compartment, and along the narrow gangway down the middle of the deck. Everywhere men were netting their gear or lounging in hammocks slung from the low beams overhead. Like a cat, Moran had chosen a corner, up against a bulkhead and quite private by local standards.

‘Here we are, sir,’ he had said, ‘the finest room in the hotel.’

It was like climbing into a kitchen range, and not a large one either, but this tight little cranny was to become as much of a home from home as my own berth over the next few days. It was here that I came to know many of the future heroes of the Birkenhead, and a fair few of the villains as well, not that the company of thieves and murderers was in any way remarkable to my experience by then. But whether good, bad or, like me, somewhere in-between, I cared little for their moral disposition as long as they talked to me. And in that way something of these young men is preserved, for in under two months most of them would be dead.

Click here to read Chapter III

Pingback: Shark Alley: Chapter One – Stephen Carver: Author, Editor, Teacher