The buildings and courtyard of the Marshalsea had a much more pleasant aspect than usual the morning after the first night I spent in the bed of Flashy Nanse. Even though I had not slept, my senses seemed strangely acute as I quit her room and walked softly into the frozen dawn. I had left my lover sleeping heavily, and had taken leave of her soft warm body only by a tremendous effort of will, based upon duty to my sister, my promise to David, and my fear of being surprised in Nanse’s bed by Bill, the man I took to be her husband. Despite the latter trepidation, I left in a state of elation that I had not known before, exceeding, as it did, even the feeling of triumph and excitement I had experienced when my first story had seen pay and print. I had travelled far and learned much in the space of that short and single night, and I was deliciously aware that I was returning to the world changed. My life, I was sure, would never be the same again.

Snow had fallen during the night, and lay thick, glowing and undisturbed on the external staircases, the slate roofs of the barracks, and the courtyard square. I paused to take in its virgin beauty, but wary of leaving an obvious trail from Nanse’s door as much as disturbing the purity of the scene, I kept to the edge of the steps, and then hugged the wall as I made my way home. Snow was not black in those days, as it is in London now, and this soft white shroud, that made even the Marshalsea glorious, was perfectly pure, like a fresh sheet of expensive stationary. The air was sharp and silent, and it felt to me just then as if I were the only conscious being in the great city, whether within or without the high spiked walls that contained me. At that hour, everything around me, whether man, beast or insect, was dreaming, dying or dead.

I let myself into our cell silently. I had learned to move about the room as a phantom, for the brief period when only I was awake was an essential and sacred moment of peace before my long day began. In my present state, a spiritual and sensual alchemy of alcohol, love and lost sleep that I have since found no drug to match, I particularly wished the night to have no end. I prayed for the chance to briefly re-live the last few hours in secret and solitude, before my return to the grind of prison life and my duties as my sister’s keeper.

Sarah was now just past three years old, and knew nothing but the Marshalsea. Her pleasing features, framed by long golden hair, suggested that she had retained her originally angelic nature, but I fear she had learned from her elders. She was now easily frustrated and subject to fits of terrible rage, while at other times she was unusually quiet and withdrawn, although when she did talk she was remarkably articulate. She also affected an imaginary friend called ‘Carol,’ who, she explained, also lived in the prison. It seemed a harmless bit of fun, and at least Carol could get a few words out of Sarah, which was usually more than we could.

I had a ritual of domestic tasks every morning that began as soon as I rose with the lighting of the fire. I would then boil water for the preparation of Sarah’s breakfast (usually porridge, or bread mashed with warm water on a bad day, and some dried fruit if I could get it). This I followed by washing and dressing. Sarah would usually wake the instant I moved from my bed, which was why her food always came first (for patience is not a virtue among infants), and if she surfaced in a good humour I would leave her in her cot to babble away to Carol while I made a brew, sometimes placating her with a knuckle of bread. If, on the other hand, she awoke discomposed and complaining, which was more usual nowadays, then I would have to get her up, fed, changed and entertained immediately. Were I lucky, she would sleep through all the stages of the ritual, and I would be left in peace to take tea by myself. When she snapped into consciousness before me, whether happy or sad, I would be most put out. The ritual would then be rushed or broken and I would spend the rest of that day feeling as if I were losing a race. More recently, I also needed to compose myself each morning before facing the increasingly awkward interactions with my father, as we broke our own fast on dry bread and black tea.

But today was different. We had a guest.

Asleep the boy looked younger, the inadequate blanket pulled up about his face to mask him from the cold, his dark curls wild and girlish. I shook him awake as gently as I could and his expression went from tranquillity to panic in an instant. ‘It’s Jack, mate,’ I said, ‘I’m a friend, remember?’ He relaxed and sat up in the bed rubbing his eyes.

Then the panic returned. ‘What is the hour?’ he said.

‘Not much past dawn,’ I told him, ‘no more than six.’ At this statement he became again agitated, and untangled himself from his blankets as if trapped in a net.

‘I must be at work at seven,’ he said in an anxious whisper, at least mindful that my sister was still, miraculously, asleep.

What job, I wondered, could instil such fear in one so young? This was hardly a deep insight, for at that stage in my life my experience of the lot of the urban poor was extremely limited. As I later discovered, children much younger than this worked, if they were lucky, otherwise they begged and starved on the streets, or worse.

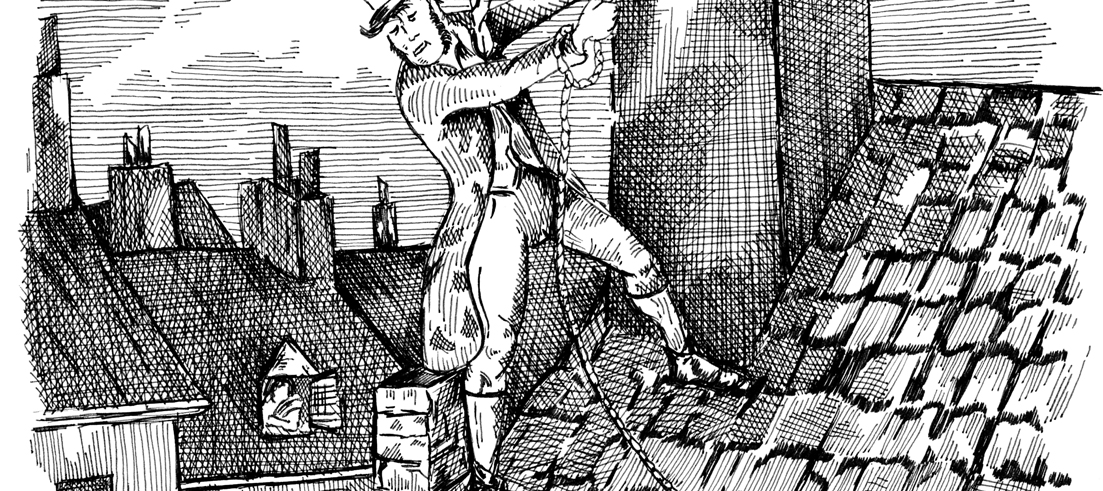

The boy had at least three miles to cover, in his estimation, and his face fell when I told him of the snow, for he was woefully underdressed for winter walking. He fretted about the time that the adverse weather conditions would most likely cost him, but I managed to convince him to at least stay long enough to take some tea and a bit of dry toast to fortify him upon his journey back into the mysterious world beyond the walls of the prison, which was, he explained, just off Borough High Street. He must then, he said, walk north along the high street, then up Southwark Street, over Waterloo Bridge, and then along the Embankment, until he must enter the dark, labyrinthine rookeries that lay hidden and filthy behind the Strand, all names that were common cultural currency about the prison, but which meant nothing to me. London was then to me a shadow, a smudge within the blur of my memory of arrival and incarceration. I might as well have been living upon the surface of the moon for all I knew of it. Finally, the boy must descend to the very edge of the foul water of the Thames by the Hungerford Stairs, where stood his place of employment, a rotten and rat-infested factory that avoided falling into the river itself, he told me, with genuine horror in his eyes, only by the intervention of great bars of wood reared against its walls.

‘It sounds worse than this place,’ I said, and then wished I had kept my opinion to myself, for the poor creature looked so forlorn I was sure that tears would soon be forthcoming.

‘It is, Jack,’ he finally said, with an accent so refined that it was difficult to associate anyone speaking thus, especially a child, with manual labour, ‘much, much worse.’ His family must have fallen very far indeed, I thought, although he volunteered no more on the subject and I did not push him. He carefully finished his toast, and prepared to go. Sarah was stirring so I dare not walk him to the gate, although he promised me that he would find his own way. This was fair enough, for you could see it from our door. I found him a spare jacket and insisted that he wore it. It buried the poor thing, but at least the weight of it would warm him up, if it did nothing else. He shook my hand at the door and thanked me very formally. ‘I do hope I shall hear more of your fine story,’ he said.

‘Then you must visit me again,’ said I, ‘if you’ve a mind to.’

‘I would like that very much,’ he said, and then he was gone.

I wondered what would become of him out there in the cold. I considered seeking out the strange boy’s father later, but then thought better of it. I had my own problems.

Then Sarah woke, in good humour, and my working day began. ‘Hullo gorgeous,’ said I, sweeping her up out of her cot. She snuggled in my shoulder and I enjoyed the feel of her soft hair and warm skin on my face as she pointed at the wall and named things that only she could see.

‘Doggie,’ she said, emphatically, for she had lately encountered a mongrel at the Gate House Lodge and was now fascinated by the things. To Sarah, all animals, real, represented, or imagined, were dogs, including the vermin we often saw in the courtyard.

‘Carol’s mummy,’ she had recently told me, ‘said they was all puppies, and I mustn’t be scared.’

I had assumed this originated from one of the women in the prison, for what else could you tell a child who might be afraid of the rats? ‘I don’t think I’ve met Carol’s mummy,’ I said.

‘Don’t be silly,’ Sarah had earnestly replied. ‘Carol’s mummy’s gone to Heaven.’

I thus looked about for a rat, but saw none. The bloody things have probably all frozen to death, I thought, setting Sarah down upon my lap to feed her. Shortly thereafter I became uncomfortably aware that her night time napkin was leaking.

‘Merciful heavens,’ said my father, rising at last, ‘but there’s a stench in the air this morning and no mistake.’ He approached the fire cautiously, but smiling.

I nodded in reply.

‘Morning Daddy,’ said Sarah enthusiastically.

Apparently we were to pretend nothing out of the ordinary had happened the night before, as was now often our way on Sunday nights and Monday mornings. It was a familiar pattern. My father was a morning person by nature, and tended to wake in a reasonable humour, but as the day progressed the black depression that now ruled him would slowly annex his soul, until by the evening he was either silent and desolate or excitable and violent.

‘Mayhap the Fleet Ditch has overflowed again,’ he said, pouring himself some tea while I attended to Sarah. ‘God’s trousers,’ he continued, peering at the filthy napkin and wrinkling his nose theatrically in an approximation of a good humour I knew to be artificial and temporary, ‘it’s a wonder you have any bones left, my girl.’

Sarah giggled and stuck both her hands in her own bodily waste. My lack of sleep suddenly caught up with me. Between my father’s barometric mood swings and my sister’s on-going toilet training, this had ‘long day’ written all over it.

*

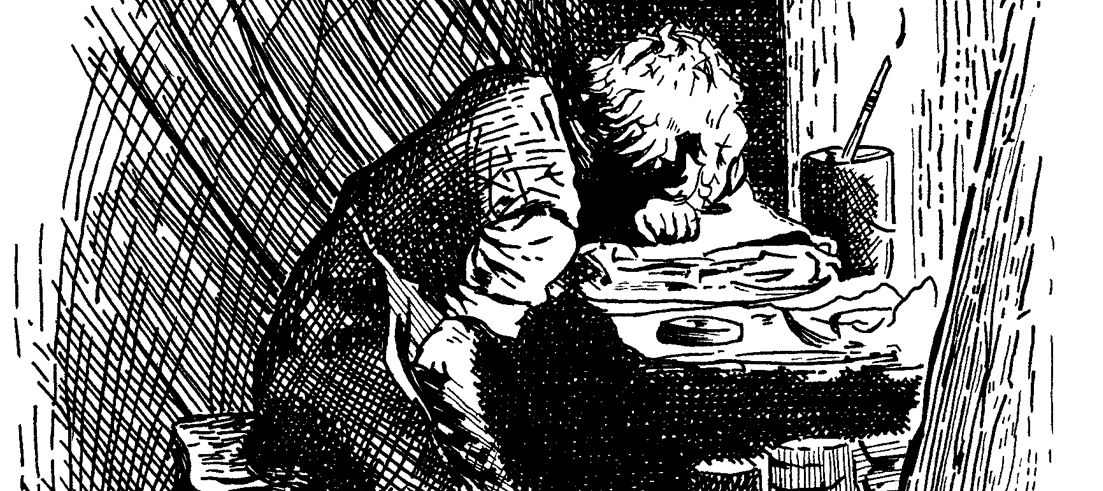

Sunday evenings now became my reason for doing anything, and much of the time that I snatched while Sarah slept was devoted to scripting the next instalment of my serial, either in my head or on paper when I could get it. I wrote around my little sister and the other domestic tasks that my father expected of me, which included all the duties traditionally associated with the lady of the house. I acquired food, by a variety of means in which non-circuitous purchase was but one option (there was also begging, bartering and theft), I cooked, and I cleaned, and when not skivvying I was often obliged to help my father tailor. I was thus, like working class women, doubly exploited under capitalism, for I kept house and also worked. My writing in that period was therefore rather episodic in structure, the text a series of brief, incremental units of narrative constructed around childcare and basic survival.

Sunday evenings now became my reason for doing anything, and much of the time that I snatched while Sarah slept was devoted to scripting the next instalment of my serial, either in my head or on paper when I could get it. I wrote around my little sister and the other domestic tasks that my father expected of me, which included all the duties traditionally associated with the lady of the house. I acquired food, by a variety of means in which non-circuitous purchase was but one option (there was also begging, bartering and theft), I cooked, and I cleaned, and when not skivvying I was often obliged to help my father tailor. I was thus, like working class women, doubly exploited under capitalism, for I kept house and also worked. My writing in that period was therefore rather episodic in structure, the text a series of brief, incremental units of narrative constructed around childcare and basic survival.

The problem of paper was finally solved by a female enthusiast in her middle years, who visited the prison attended by a strapping servant with the intention of distributing bibles by which we poor sinners and fallen souls might learn the error of our ways, and be lifted up once more to the bosom of our Lord and Saviour.

‘God bless you, madam,’ I said, when I received my copy, with genuine feeling, for I really needed that book. I grasped her frail hands in heartfelt thanks and obviously disconcerted both lady and servant, for the former appeared suddenly quite flustered while the latter pulled me away roughly and called me a ‘dirty fucking beggar’ under his breath.

‘That wasn’t very Christian,’ I told him.

Those bibles were of inexpressible aid to myself and my fellow sufferers. The pages were soft, strong and absorbent, and the good book therefore became a source of great solace for anyone visiting the long-drops at the back of the yard for months afterward. Equally, paper stuffed between layers of ragged clothing was a wonderful insulating agent against the ravages of the endless cold. You could read it too, although, as I had learned to my advantage, that was quite a rare skill in these parts.

In my case, after much experiment on single sheets, I developed a system of deinking based upon soaking the pages, by means of personal micturition, until the print was reasonably faded, then rinsing them thoroughly in rainwater and pegging them on string across a corner of the room to dry. (That’s a technique you will not find in any guide to literary composition.) My father said I would most likely be damned, but I replied that we already were. Try not to judge too harshly though, but instead reflect on the user and commodity value of paper in the subterranean regions. That good lady did indeed do the Lord’s work by easing the suffering of the poorest of the poor, and is not that, in the end, what Christ urges us all to do? It is more to the pity that we could not eat the things, for that would have saved many back gate paroles that winter.

Ink I made from rainwater and soot, and my quills were cut from pigeon feathers gathered in the courtyard or traded with other prisoners, once the word was out that I needed such things. Sometimes I would be presented with an entire bird, which we would eat if it did not seem too game. The consensus of opinion in the snuggery was that I was building a machine for the purpose of self-pollution. While I stammered out my protestations and explanations, my Nanse would just smile.

The Shivering of the Timbers therefore continued, getting sillier with every passing instalment. My protagonist fell through time and was found by pirates adrift in the Indian Ocean, having spent the next and linking part of the narrative upon a raft fashioned from driftwood and fighting a giant shark. After a long battle of wits, he eventually bested the beast with a harpoon improvised from a shattered mast. Fortunately, the debris of his ship, which had similarly travelled through the magical portal, was no longer possessed. That was a bit of a yawning plot hole, but I managed to get away with it because everyone loves stories about sharks.

He and I then embarked upon a complex spiritual and physical journey, locked in a war of attrition with the evil ghosts, who had possessed a ship and its sailors, and in quest of a legendary grimoire. This was an ancient book of spells reputed to hold the power to exile the undead scourge and return the hero to his own time. Captain Kidd had saved the hero, and they frequently fought together, alongside other famous pirates of the day, although who they sided with was often unclear. Mary Read and Anne Bonny formed two sides of an interesting romantic triangle, much in the manner of the real-life relationship between Jack Sheppard, Edgeworth Bess and Poll Maggot, and which, had it ever seen print in the form that it was originally penned, would have seen me prosecuted for obscenity, forgetting all the other stuff that later got me into so much trouble.

My new friend David never missed an episode, or the opportunity to afterwards explain its many structural and figurative shortcomings. ‘The point of all this blood and thunder,’ I would tell him, ‘is that if you must write for the mob then you must not write too weak.’

He tended to damn with faint praise, suggesting that my talents might be better employed in more serious literary endeavours. ‘But why, my dear Jack,’ he would say, ‘do you insist on writing about nothing but pirates?’ That was a good question, and it has been asked since, repeatedly, and with considerably more judgement, derision and downright venom behind it that when first raised by my young friend all those years ago.

‘For money, of course, you needy-mizzler!’ I would reply. What did he think we were in here for, the pillock?

There was also my outcast’s natural affinity for the outlaw, or at least the romantic image of the outlaw, who I always saw as a rebel and a class warrior, never just a thief and a murderer, which was invariably the truth of the thing. I was also writing for love, for the thought of losing my special night, and therefore Nanse’s affections (for the two things had become inextricably linked in my young mind), was a constant source of anxiety. I already knew, you see, even back then, that a writer is only ever as good as his last story. The patrons of the snuggery could tire of me very easily, and the last thing they wanted was the kind of contemporary social realism that was the bee in our Davey’s bonnet. This was a subject that we also discussed as much as we were able between my readings, my family, my love life, and the demands of his day job.

‘Why do your manuscripts always smell funny?’ he asked me once. I dare not tell him, because there was enough circumstantial evidence to suggest that he was a true believer, and I was in no mood for a sermon. I sniffed my papers and stuffed them quickly into a poacher’s pocket, muttering something about ‘bloody cats,’ although there were, to my certain knowledge, no such animals located anywhere within these walls. Even though the turnkeys frequently introduced stray cats to take care of the rat infestation, the inmates just kept eating them. They ate the rats too, and if there were no dubsmen about the place to keep the peace then I’d not have ruled out cannibalism either.

‘It would be my object, were I you,’ said my young companion, ‘to present little pictures of life and manners as they really are, not in some melodramatic fantasy in which every character has a clearly defined sphere of action—hero, villain, damsel in distress—and everything is resolved with such neat simplicity.’

‘Thank you, Dr. Johnson,’ said I, more than a little put out of humour by this remark. ‘Have you any idea at all how difficult it is to maintain so many story lines at one time,’ I continued, moved to defend my art in the face of its critics (a habit I have not lost), ‘half of which take place in different centuries and, indeed, astral dimensions, while obliged to tell jokes and get in a fight or a fornication every five pages or so, because you’ll lose your audience otherwise, and then come up with an ending each time that satisfactorily closes one episode while setting up another? Do you know how taxing it is to invent a character, to give him a life and a distinct voice?’ I was quite carrying the keg by then, as the locals would say of a man greatly tested and unable to conceal his chagrin. I spat on the floor and summed up: ‘It was an easier matter by far for Wellington to organise his forces at Waterloo, or for Ajax to lay waste to the Thracians. I would sooner unravel the skein of my family’s debts, or yours for that matter, than embark upon another God cursed serial romance!’

‘But could not you at least set the story in the present?’ he persisted, ‘in London, perhaps?’

‘No,’ said I, determined to be difficult. The pitiful truth was that I knew nothing of London beyond roughly where it was located on a map of England.

‘When I walk to work,’ he persisted still further, for he was a stubborn cove, even back then, ‘I see such things on the streets.’

‘What things?’ I demanded, aware that my pitch was rising in the wake of my little artistic tantrum. I was momentarily blessed with the insight that, unlike my sister, I was supposed to have mastery of my emotions. I was waiting on Nanse, who was significant by her absence, and beginning to crash like a dipsomaniac deprived too long of the drink.

‘Wonderful and terrible things, Jack,’ said he, ‘there is tragedy and comedy everywhere.’

‘Even at the factory?’ I said. That was a low blow, but it not deter him.

‘Yes,’ he said, quietly, ‘even at the factory.’

I knew all about that factory by then. In terms of my blindness to the world outside the walls, he was my eyes. I thus often saw the city as he did, with all its humour and horror, and his own sense of self-worth in relation to it. When he spoke uninhibited, which was not often then, he could already paint pictures with his words. It was a talent he told me he had inherited from his mother and his grandmother, both consummate storytellers.

It was his mother who had betrayed him though, as much if not more than his father, of whom he still saw nothing. He would receive his daughter in his cell on Sundays, but not his son, whether because of pride or indifference my friend did not know. He seemed even more alienated than I, for at least I had Sarah, and, sometimes, Nanse, providing me with some kind of rudimentary human validation. It is no wonder that the poor child had therefore attached himself to me, for his mother sent him to visit his father every week, regardless of the boy’s protestations that he was obviously not wanted. I wondered who the mother had calling that required such a need for privacy.

The factory on the Hungerford Stairs haunted us both, for I saw it as clearly as he: as crooked as an old man, rotten, damp, cold as a witch’s slit, and swarming with rats made fat off the filth of the river it abutted, the drowned, the murdered, and the suicides, always in the foul mud and dark water that lapped at the piles and posts like a hungry whore at a cock. It was into this blighted place that the boy’s parents sent him to work, for ten hours a day, two days after his twelfth birthday. As his father was useless with money and his mother had, he told me, resolved to ‘do something,’ it was clear that it was she that had been the architect of his despair, transforming his young life at a stroke from that of a promising and ambitious scholar to a manual labourer.

Shortly after that his father went into the Marshalsea as an insolvent debtor, leaving David in much the same position as I, although I was coming to realise that he had the worst of it. It was true that he did have the notional freedom to walk out of the main gate during daylight hours, and was not obliged to return in the evening, but he was at liberty only to travel between an unhappy and neglectful home, and a loathsome house of miserable toil that was no less of a dungeon to him than my own place of incarceration. We were both of us in chains forged by our elders.

Likewise in common with me, my friend would protect himself by withdrawing into the realm of his own imagination, although whereas I tended towards the fantastic he favoured a kind of embellished realism, by which he created biographical sketches of those around him through a blend of conjecture and often staggeringly acute observation. His flair for describing places was matched by his eye for people, and through our conversations I felt as if I knew the staff of the factory as well as he, from the avaricious and falsely benign owner, to the ambitious charge hands that harried him constantly to work faster, and his fellow labourers, who quickly ostracized him on account of his ‘airs.’

We did the same thing with the clientele of the snuggery, looking at mannerisms, inventing histories, and drawing grotesque caricatures with words. ‘See that one—’ one of us would begin, looking discreetly towards a likely victim, sometimes known to us, and sometimes not. We would then extemporise a character study between us, taking turns at the crease, until we eventually collapsed into helpless and ill-disguised giggles, our ages betrayed, just for that moment, by a youthful joy that could still resist the creeping cynicism of our circumstances.

Bertie the Badger wrote himself. ‘We are quiet here, my friends,’ he was fond of saying, to any new arrivals, and plenty of old ones as well, although we’d heard it all before. ‘We don’t get badgered here. There’s no knocker, sir, to be hammered at by creditors and bring a man’s heart into his mouth. Nobody comes here to ask if a man’s at home, and to say he’ll stand on the door mat till he is. Nobody writes threatening letters about money to this place. It is freedom, sir, it is freedom!’ Bertie’s thesis was simple: ‘We have got to the bottom,’ he would say, ‘we can’t fall no further, and what have we found? Peace. That’s the word for it,’ he would triumphantly conclude. ‘Peace.’

This, I recall, particularly got under my friend’s skin. ‘Are we really at the bottom, Jack?’ he asked.

‘I’d probably better not answer that,’ I said.

There was a serious point to all this though. We were both, after our own fashion, turning to the idea of somehow writing politically, although neither gave it a name at that point.

Our original experiments were primitive, to say the least. There was no real satire in my early stories, and I tended to see factions in society that oppressed my class in terms of personal vendetta, so did not get much further initially than naming villainous characters after my enemies. Traitors, turncoats, corrupt politicians, and wicked noblemen tended to be either physically modelled upon or named after my family’s landlords and solicitors over and over again. David was much the same. Although he had a natural eye for detail, his observations seemed more to the purpose of aiding and easing his own understanding of his revised position in the world. He would invent alternative versions of his own life, he admitted, which he would adopt when between factory and prison. So to tradesmen along the route with whom he conversed, he remained a middle class schoolboy with prospects.

On one visit he was particularly excited, not to say slightly pissed, having just spun a convincing yarn to a publican and his wife on Parliament Street about it being his birthday.

‘They asked me a good many questions,’ he reported, ‘what my name was, how old I was, where I lived, and how I was employed. To all of which, that I might conceal my true station, I invented appropriate answers.’

‘And they fell for it?’

‘They made me a gift of a glass of their very best ale,’ said he.

‘You’re learning,’ I said.

Inevitably, David pointed out Bill and Nancy quite early on. They did stand out somewhat. ‘Let’s do them,’ he said.

‘Can we not,’ I said, ‘they’re me mates.’

He looked to another subject instead, Penelope, a naturally morose woman who had some kind of connection with Bertie and who I assumed to be on the bash, only lower down the local hierarchy than Nancy. ‘Nelly, then,’ he began, ‘not a natural blond, of course—’

But I could have done Bill and Nancy. I was beginning to grasp the complexity of their relationship, and a sense of myself in relation to it that was far from reassuring, for I did love her, in my way, in much the same way that I would later love opium.

My insights began one night as I lay with her, our sweat cooling as we drank gin in bed and shared a long pipe. ‘I have a son about your age,’ she had said.

It crossed my mind that she might be referring to Freddie, the obedient puppy, or Sid, who looked like a miniature version of Bill, complete with battered topper. I was wrong on both counts. She had not seen her son for years, she said, not since the death of her husband, who had been a greengrocer in Wapping. It was a familiar story. The business had failed, and Nanse, by degrees, was driven to the street to support herself and her boy. He had not understood, and in the rage that comes of adversity and a childhood lost he had denounced her as a low whore and left to make his own way in the world. She knew not whether he had lived or died, although she carried with her his youthful likeness in a pewter spinner about her neck, purchased in better days, with her own miniature portrait, as fresh as it was foreign, on the opposite face. He looked a bit like me, the same sharp features, dark hair and eyes. She had been stunning.

‘I do like my young men.’ She would say, while toying with my hair or stroking my skin.

She had a way of talking about other men that was both disconcerting and exciting, especially the pretty boys, whom she preferred, but soon discarded. Our foreplay would often involve anecdotes about previous lovers and clients, and I would hate her for it and want her more than ever. She would start to breathe deeply and tell me that I was the best, and, like an idiot, I would believe her, secretly thrilling at the thought of all the dirty things that she had done, and at what a fine young buck I was for stealing her heart away.

Needless to say, I knew what she did, and often with whom, but I also knew that I was special, for no money ever passed between us. It was Bill, who I had cast in my own mind as the cuckold, who popped that particular bubble one night in the snuggery, when I asked him for a modest raise. I had gathered from Nanse that he was charging the audience considerably more than he had admitted to me when we entered into our partnership.

‘Aren’t you getting more than enough already, son?’ said he, with an evil leer, nodding casually in the direction of my lover.

I withdrew, humiliated, and took my leave as soon as I had finished my reading. My heart had not been in it, and my words felt witless and leaden, as befitting, I realised, something effectively written upon toilet paper. Since that night, pimps and publishers have always been linked in my mind.

I sulkily avoided Nanse, until she sought me out in the family cell, fully aware that my father was engaged for the evening as chair of the debtor’s committee. It was only Wednesday night, but those three days had been eternal. I did not rise, and remained awkwardly seated at the table where I had been sewing for my father.

She arrived quickly at the point. ‘I have something in need of maintenance, my valiant little tailor,’ she said, coming to me and placing a high-booted foot upon the table in front of my face, raising her skirts. ‘Look,’ she demanded, ‘I have a velvet purse that requires immediate attention.’

I could no more reject her than I could have turned down a drink and a smoke. I buried my face between her thighs and forget about everything, until, that is, I noticed the bruises concealed beneath her clothes. ‘What did you expect?’ she said quietly, ‘he knew it was me that blew the gaff.’

I did not discuss such things with David, although I suspect that he knew, and character studies of Bill and Nancy remained taboo, as did comments concerning our own families. We both still did it, of course, only we did not admit it to each other, for writers use everything.

Like many of my friendships, the one with David was intense but short-lived. Times must have become harder, for with the coming of the spring my friend’s entire family moved into the prison, setting up house in a similar room to that occupied by my own folk. Either the head turnkey was turning soft in his old age, or he was easily swayed by a posh accent. I think he fancied David’s sister as a match for his own boy too, which, from what I could see of her parents, was as likely to come to pass as gold raining from the heavens or an honest man entering government or the law. My friend continued to leave the prison to work in the dreaded factory, but his people wanted no association with the Father of the Marshalsea or his children, and David was forbidden to see me or to venture anywhere near ‘Book Night’ in the snuggery. Once more his mother was ‘doing something.’

Our continued contact therefore became as clandestine as my early relationship with Flashy Nanse, with snatched and secret meetings, out of sight of watchful eyes. This was a small barracks however, and there was no way to avoid each other in reality. The trick was in how one might contrive the meeting to appear accidental, so that David might avoid a beating from his father while his mother drummed into him with equal if not more force her maxim that although his family was in the Marshalsea, they were not of the Marshalsea. I was touched that my friendship meant so much to him, but I needed him as well. Writers are for each other. No other bugger understands us.

Click here to read Chapter XII

No Comments